Pioneer Profiles – July 2021

Did you know that Jacksonville was the first West Coast group of buildings added to the National Historic Register? In 1967 it was one of eight initial towns designated as a National Historic Landmark City by the U.S. National Park Service. Over 100 historic structures were identified as comprising Jacksonville’s National Historic Landmark District, and over 600, both inside and outside of city limits, were identified as contributing to the character of the town we know and love today.

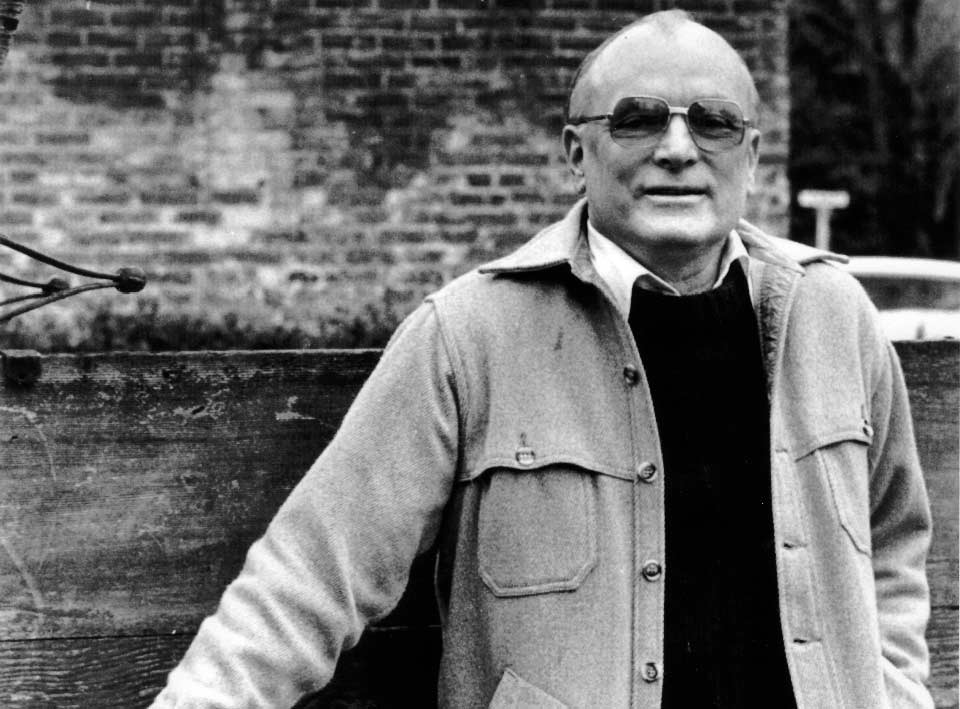

It took a village to make this happen, but much of the effort can be attributed to one individual, Robertson E. “Robbie” Collins.

Robbie Collins was born in Riverside, California, in 1922, graduated from Stanford University following service in World War II, and worked for a year in San Francisco before moving to Jackson County in 1948. He joined his brother in the lumber re-manufacturing business, turning waste wood from local sawmills into specialty wood products. According to Collins, they were just trying to make a living. Looking back, however, he recognized they were also in the conservation business.

Collins had become interested in preservation by 1962 when he moved from Central Point to Jacksonville, purchasing the historic Kahler Law Office on North 3rd Street for his initial residence. At the time, Jacksonville was literally the “wrong side of the tracks.” The town had become a backwater after the Oregon and California Railroad bypassed Jacksonville in favor of Medford and the flat valley floor.

Soon after Collins moved, the Oregon Department of Transportation announced plans to put a four-lane highway across eight city blocks, bisecting Jacksonville and destroying 11 historic houses. Robbie led the group that spearheaded the opposition. He later admitted that he did so “not out of a sense of history; I just really didn’t want a four-lane road that close to my new home.”

“Lie-ins,” protests, and national media coverage defeated the proposed highway. An angry Glen Jackson, head of the State Highway Commission, subsequently challenged Robbie: “Now that you have saved that damn town, what are you going to do with it?”

Collins later recalled, “The people of Jacksonville thought they were living in a town that wasn’t important.” Some residents just wanted to “get rid of the old buildings and renew the town.” Although still viewed as an outsider, Collins challenged the community to develop a sense of pride and to value Jacksonville’s unique history.

Rebuilding community pride began with the founding of the Jacksonville Boosters Club with Collins as its first president. While gaining community support through parties and socials, the Club created an initial vision of what Jacksonville could be.

By 1964 Collins was one of seven trustees on a newly formed Jacksonville Trust for Historic Preservation. Their first project was the “rehabilitation of the U.S. Hotel.” At the time, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) was doing model city projects and wanted to include an historic town. Although Jacksonville was picked as the model historic city, HUD didn’t want to touch the hotel—too big, structurally condemned, and slated for demolition.

But Collins saw a way. He had Mayor Curly Graham arrange for an appointment for the two of them with the Chairman of the U.S. National Bank in Portland. The goal: having the bank open a branch in Jacksonville. And what could be a more logical site than the former U.S. Hotel?

A foundation was set up for the project. The city sold the building to the foundation for $1. The U.S. Bank agreed to open a Jacksonville branch, to pre-pay 10-years’ rent ($25,000), and to make the bank a replica of an early 1900s bank. Local orchardist and philanthropist Alfred Carpenter loaned the foundation another $25,000 knowing he would probably not be repaid. With those monies (and more from local organizations and individuals), the U.S. Hotel—including the ballroom and hall—was restored, the turning point in Jacksonville’s resurrection.

The multiple events heralding the 1965 reopening of the U.S. Hotel were the biggest thing in the Valley in years, attended by movie stars, Miss Oregon, the owner of the San Francisco Chronicle, big corporation people from Portland, and all of Medford. The hotel’s restoration became the centerpiece in the 1967 establishment of Jacksonville’s Historic Landmark District.

And the world began to take note of Robbie Collins.

Collins spent two years as a West Coast advisor for the National Trust for Historic Preservation before becoming a board member for 11 years. He served on many national, state, and local historic boards including the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, the Portland Art Museum, and the Southern Oregon Historical Society. He received a University of Oregon Distinguished Service Award and was recognized by the Governor of Oregon with a Distinguished Preservationist Award. He became a founder of the 1000 Friends of Oregon, promoting land use measures to ensure the livability of cities and towns while protecting working farms, ranches, and natural areas.

Collins became an internationally known lecturer and preservation expert. As he approached retirement, he began accepting overseas projects where he could use his Jacksonville and small-town experiences to assist third-world countries in their attempts to save their historic sites. He also became the Chairman of the Cultural Tourism Committee of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (“ICOMOS”), an august group dedicated to these purposes.

Upon retiring from his lumber business at age 63, Collins devoted full time to the international front. After serving as a consultant for the Pacific Asia Travel Association, his second career led him to settle in Singapore, “a mix of tourist development and heritage conservation” that proved an outlet for his passion. With Singapore as a base, he became a teacher and consultant on historic preservation for Singapore, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Thailand, Fiji, the Philippines, China, and other Asian countries.

However, Collins never forgot Jacksonville, the town that started him on his crusade. He returned often to Jacksonville, and in 1987, he and his good friend Marshall Lango embarked upon a project to authentically recreate the Beekman Express building and the adjacent law office at the corner of California and South 3rd streets.

Beekman’s Express, the oldest financial institution in the Pacific Northwest, was the 1856 successor to Cram & Rogers Express Company. Cornelius Beekman had taken over the Jacksonville to Yreka route when his former employers went belly up. Both businesses handled the shipment of gold from Jacksonville area mines with Beekman subsequently purchasing gold and shipping it on his own behalf.

The original building had been severely damaged in an 1895 windstorm and later demolished, so Collins, Lango, and their team had little to go on. They studied early fire insurance maps, 1800s newspapers, Peter Britt photos, and an 1856 lithograph to create a scrupulously accurate building exterior. For the interior, they used research and imagination to create a building that would have the feel of yesterday yet meet current building codes and make sense today.

They took 13 years to do things right. Eastern white pine boards were hard planed and square nailed; old growth timber for floor planks was culled from a Native American reservation in northern Oregon; hand split roof shakes were specially logged. Collins financed the project, saying “going first class always pays off in the details” and “this one won’t come down in a windstorm.”

Collins and Lango agreed that they would declare the project completed with a celebration that included the city’s lighting a replica of Jacksonville’s gas streetlight at the 3rd and California street corner. The celebration took place on May 23, 2003.

However, Collins was not able to participate. He died that same day in Singapore of dengue fever. He was 81 years old.

On August 17, 2003, Robertson E. Collins was posthumously given the first annual Southern Oregon Heritage Award for his outstanding commitment to preservation and the promotion of history. The Robertson E. Collins Foundation Fund for Historic Preservation was also established by friends and family to support preservation and education projects in keeping with Collins’ vision.

Pioneer Profiles is a project of Historic Jacksonville, Inc., a non-profit whose mission is to preserve Jacksonville’s Historic Landmark District by bringing it to life through programs and activities. Join us this summer for our 1-hour Walk through (Jacksonville’s) History tours every Saturday at 10 am and our Jacksonville Haunted History tours the 2nd Friday of each month. You’ll find tour information, blogs, upcoming events, and more at www.historicjacksonville.org!

Hi Carolyn,

You’ll be surprised to receive this email from Singapore . Robbie came to Singapore with the late Pete Wimberley and George Lipp as part of an International Task Force by invitation of the STB [ Sing Tourism Board ] to study the conservation of Singapore’s Chinatown , Little India and also Kampong Glam , the Arab/ Malay quarter . That was in 1984. I met Robbie in 1986 at the opening of a Building which I helped to conserve, now a National Monument . I knew Robbie until his untimely death during the height of the SARS outbreak . But you were right he passed away due to Dengue fever and not to Sars.

Marshall Lango kindly sent me the piece you just wrote . The conservation of Jacksonville as a heritage township to my mind is incomplete without the mention of Larry Smith and also the late Eugene Bennett, two individuals I have had the pleasure to meet . They added a special flavour to the promotion of the Arts in Jacksonville and also to the conservation of the environment and eco-system around Jacksonville. If you walk through the woods now , you’ll be able to find a bench with my name on it. I found the spot enchanting because it told the story of the gold rush in the Rogue Valley which gave the town and Beekman Express the reasons for their existence.

I love the piece you wrote about Robbie which brought back so many memories. It’s hard to imagine he died 18 years ago and now, we are having to cope with a sequel to the Sars pandemic. So take good care and stay safe either from the virus or the heatwave !! Thanks once again of writing so fondly of Robbie . Did you ever meet him ? A truly rematkable person who gave more than he ever received . A Buddha without being a Buddhist !!

Warmest regards ,

ST