On Real Estate & More – April 2020

As a real estate agent, I am frequently asked to explain how property taxes are assessed. Oregon’s complex property tax system doesn’t always make it easy to figure out, but the property tax system is one of the most important sources of revenue for Oregon. The following is a summary of Oregon Property Taxation (from Jackson County Assessor website).

Prior to 1991:

- Taxes were based on Real Market Value (RMV), which is the estimate of what a property could sell for.

- Taxing Districts could raise their revenue by 6% annually. If they wanted more than 6%, they needed voter approval.

1991 Measure 5 (M5):

- M5 still based the amount of taxes on RMV. However, Measure 5 created a cap on the amount of monies taxing districts could receive if they passed a certain limit.

- The categories were broken down into Government and Education.

- The initial fiscal year of 1991-1992 placed a limit of $15 on Education and $10 on Government.

- In 1995-1996 the cap had ratcheted down to $5 on Education while Government stayed at $10.

- If a property reaches its limit on either category, taxes above that limit are compressed off the tax roll.

- Education experiences far more monies compressed off the tax roll than government.

- Measure 5 still is in effect today.

1996/1997 Measure 47 (M47) and Measure 50 (M50):

- In 1996: M47 was voted into law. However, major flaws existed in the law and in 1997 a revised form M50 was voted into the Oregon Constitution.

- Prior to M50, taxes were based on RMV. M50 created a 2nd value on all property called the Maximum Assessed Value (MAV)

- If a property existed in 1997, the MAV was established by taking the 1995 RMV – 10%.

- Once MAV is set on a property, it grows by 3% annually.

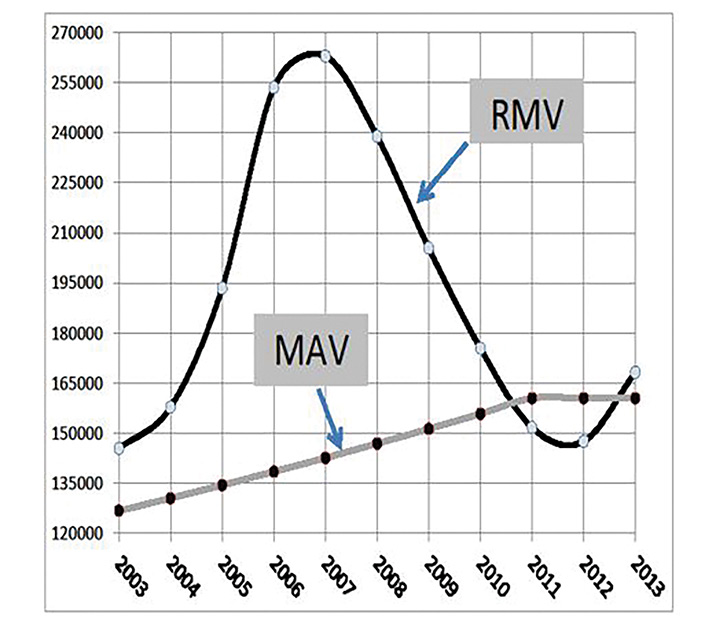

- The 3% rule has a pro and a con: When the real estate market is robust, the assessed is limited to the 3% growth. However, when the real estate market collapses, the RMV plummets but the MAV still grows. MAV is set, the only way for the tax burden decrease on property is if the RMV falls below the MAV. (See graph.)

Assessments can differ. The 1997 ballot measure approved by Oregon voters separated taxes from the real values of homes. Instead, it pegged taxable values to 1995 levels, plus 3 percent a year. As a result, most homeowners can expect a 3 percent increase each year, regardless of what happens to market values. But property owners don’t share the benefits of those ballot measures equally. Here are a few ways your tax bills can change over time.

If you renovated your home, any work valued at $10,000 in one year or $25,000 within five consecutive years can trigger a new assessment and increase your property’s taxable value. This can include improvements made in previous years that county assessors missed at the time.

If voters agreed to a new levy or bond, you’re going to see that reflected in your property tax bill.

Property taxes are capped as a proportion of real market value, as determined by the county assessor. The property can only be taxed $10 per $1000 of real market value for general government and $5 per $1000 of market value for schools. (Certain temporary levies and bond measures are exempt.) If you hit that cap, you’re benefiting from the 1990 tax-relief measure known as Measure 5.

But if a property’s market value rises quickly, that cap can rise just as fast — much faster than the 3 percent a year homeowners might expect.

If you have questions about your property tax assessment, contact the Assessor’s office.

Sandy J. Brown lives in Jacksonville and is a real estate broker and land use planner with Windermere Van Vleet Jacksonville. She can be reached at sandyjbrown@windermere.com or 831-588-8204.

Sandy J. Brown lives in Jacksonville and is a real estate broker and land use planner with Windermere Van Vleet Jacksonville. She can be reached at sandyjbrown@windermere.com or 831-588-8204.