Pioneer Profiles – March 2022

It’s March and spring is in the air! The daffodils and forsythia are blooming, and the birds have on their “mating colors,” so Love seems an appropriate topic for this month’s Pioneer Profile —although in this case the Love in question is John Love and the Love family.

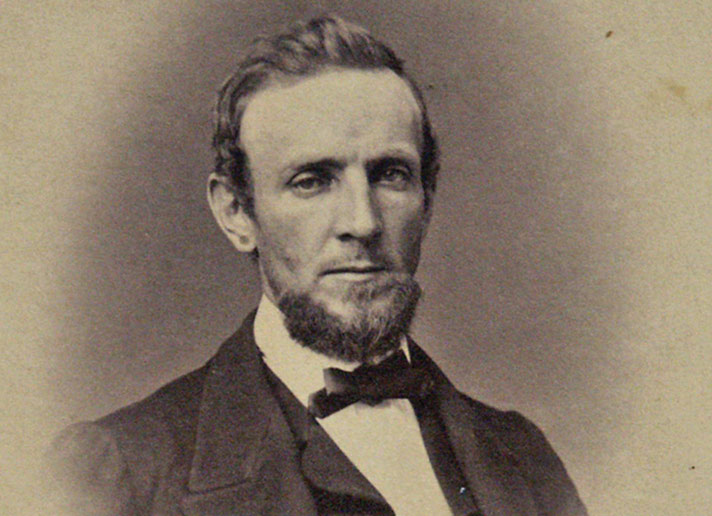

John Swan Love was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1830.

He had already established himself as a merchant at the age of 20 when he, like so many other young men, heard the call of the West. With miners and settlers heading to Oregon, merchants were obviously needed!

He had arrived in Jacksonville by 1854 and by 1856 was in partnership with John Bilger. Together they purchased space in a row of shops roofed under one or two wood frame buildings on the north side of California Street between Oregon and 1st streets—an assemblage of shops then known as “Kennedy’s Row.” Mathew G. Kennedy, the first elected sheriff in Jackson County, ran a “tin shop” at what is now 150 W. California which he sold to Love and Bilger. The “Love and Bilger Tin Shop” became actively engaged in selling “tin plate and sheet iron works to the public.”

Their partnership initially extended to housing as well, what with early town emphasis being on building businesses, leaving residences in short supply. They may well have boarded with Mary Ann Harris and her daughter since an 1860 census shows Love, Bilger, and Mary Ann and Sophia Harris all sharing a residence. Mary Ann Harris and her then 12-year-old daughter Ann Sophia had taken refuge in Jacksonville after an 1855 Rogue Indian War attack on the Harris family’s homestead killed Mary Ann’s husband and son. 1856 records show Mary Ann purchasing the house and lot at the northeast corner of North 3rd and C streets.

Apparently, Love initially became the “public face” of the partnership. He seems to have been involved in town governance from its early days and when Jacksonville was incorporated in 1860, he became a town Trustee. He served on committees responsible for securing plans to build the town recorder’s office and fire station and inspecting and adopting the 1862 town plat. He was also instrumental in establishing the town cemetery.

It’s unclear whether John’s father died or his parents separated, but his mother, Margaret Swan Love, apparently came west with John. When Margaret died in 1859, the city could not refuse Love’s request to bury her in the town’s new cemetery, even though the cemetery was not officially open. The need for interment didn’t hinge on whether the cemetery was ready, and the necessary formalities completed. The city granted John permission to purchase a lot. David Linn, the local cabinet maker and builder, supplied a deluxe wooden coffin, lined with white muslin and covered with black velvet, and the remains of Margaret Love were laboriously carried through the rain up an Indian trail to the top of the hill. She was the first person to be buried in the Jacksonville cemetery. The tall marble monument that adorns her grave was shipped around Cape Horn from Italy and came overland by freight from Crescent City.

But Love’s political interests were not limited to Jacksonville. He played an active role in the regional Democratic Party and served as a Jackson County Commissioner from 1860 through 1866.

Having a tin plate and sheet iron business proved profitable as did ties to local government. Jackson County Commissioner records show Love & Bilger regularly supplying both city and county with “sundries for the courthouse,” “spikes for the road district and bridges,” “materials for repair of county offices and jail,” “furniture for public buildings,” and other goods and services. Love supervised alterations in the County Jail designed to improve ventilation in the prison’s cells and “to render [the building] more secure against the escape of prisoners confined therein.” He is also on record as having been reimbursed for “services related to insane persons.”

Meanwhile, Sophia Harris grew into a lovely young woman. One week after her 16th birthday, the 29-year-old Love married her on February 23, 1860.

Four children soon followed—George, John, Maggie, and Mary. Although by this time Bilger was no longer a boarder, having constructed his own home on Blackstone Alley, John soon found living with his mother-in-law too crowded. In 1865 he obtained title to the northwest corner lot at North 3rd and C streets from James Clugage, the original donation land claim owner of most of the township. A year later he acquired ownership of the adjacent lot. Soon after this, John had the present residence at 175 South 3rd Street built for his family—kitty-cornered across from his mother-in-law.

But John, Sophia, and the children did not have long to appreciate their fine new residence. On September 18, 1867, John died from tuberculosis. Sophia was pregnant with their youngest child at the time of John’s death. John’s funeral was reputedly one of the town’s largest, and fellow townsmen lauded him as follows:

“Our old townsman and friend John S. Love was buried yesterday. His death is a public loss, as he was a good & upright citizen. His death makes a great void in our community. His place cannot be filled. We all miss him much.”

John Bilger took over the tin and hardware business. Sophia and the children moved back into her mother’s house across the street. Her mother had remarried Aaron Chambers, a farmer and widower in 1863, and was now living on Chamber’s farm on Hanley Road.

Sophia inherited John’s estate, but then, only 15 months later, Sophia and their younger daughter Maggie died within days of each other—victims of the 1868-1869 smallpox epidemic that took the lives of many Jacksonville residents.

According to the nurses who witnessed three-year-old Maggie’s death, the child “brightened up and commenced talking to her mother. No one was in the room but the two nurses, but the child insisted that her mother was standing at the foot of the bed and had come for her. A few convulsive breaths and the little heart stood still….”

Their funeral bore no resemblance to John’s. With the fear surrounding smallpox, victims were buried at night by the cemetery sexton and local priest.

The three remaining children were raised by their grandmother, Mary Ann Harris Chambers.

This profile has a lot of surmises and ifs, ands, and buts. But Jacksonville’s early records are sketchy, particularly when the subjects died during the town’s “infancy.” Legend embroiders facts, and the story line shifts as new sources become available. Think of this story as a quilt—pieced together from the fabric scraps of history….