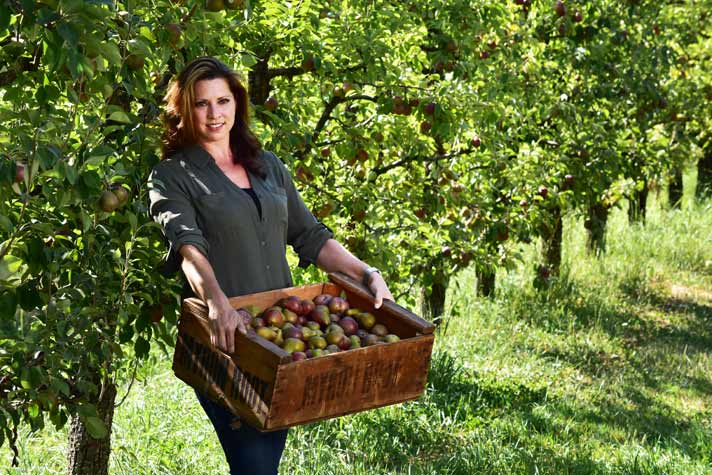

Pears are prominent players in Eden Valley Orchards’ past. Yet the future of each year’s crop faced uncertainty.

“Pears just really don’t sell,” says Ashley Campanella, winemaker for the Medford estate’s EdenVale label.

Raising the profile of pears—and preserving the fruit—entailed treating them much like the property’s 14 varieties of wine grapes. Pressing the pears’ juice, fermenting it and bottling the bubbly beverage affords EdenVale’s tasting room its first alternative to wine and Southern Oregon with its first alcoholic pear cider.

“This really, truly is a wine,” says Campanella. “It’s a pear wine that’s carbonated. You ferment it just like a wine and finish it just like a wine.”

Pressed from the 2015 harvest, about 1,200 gallons of pear juice produced 900 cases of cider slated for release this autumn. About 80 percent of those are 375-milliliter half bottles, screen-printed with a green pear and superimposed window.

The “Pear House” label provides a delicious glimpse of Eden Valley Orchards’ 130-year history as the region’s first commercial pear orchard and a vantage on the fruit’s viability in the modern agricultural era. The value that pear juice gains when converted into cider ensures the crop’s sustainability, says Campanella. Although 800 acres of pears during Eden Valley’s heyday have shrunk to a mere seven acres, the remaining trees are costly to maintain, she says.

“The pears are a part of our history… history we love.”

Consumers likely will love the cider’s low alcohol content—about 6.9 percent—in addition to its carbonation. While many pear ciders on the market actually are apple ciders with a bit of pear juice, Pear House is “pure pear straight from our trees,” says Campanella.

Eden Valley’s Seckels—scarce in Southern Oregon, but celebrated in culinary circles—mingle in the Pear House recipe with Comice, D’Anjou, Bosc and Bartlett varieties, all grown organically in the estate’s “experimental” orchard. Completely fermenting the cider until only trace sugars remain distinguishes Pear House from mainstream brands that often contain added juice or sweeteners.

“When you taste it, it does taste dry,” says Campanella.

This European-style of cider-making is helping to define a new American trend. Commonly marketed to beer drinkers who don’t want all of grain’s gluten, craft ciders are on the rise. Their recent popularity also could be a backlash against heavily-hopped beers, says Chris Dennett, owner of Beerworks in Medford and Jacksonville.

“There’s probably not enough Old World ciders available,” says Dennett, whose shop stocks Southern Oregon’s largest selection of ciders, about 40 different types from around the state and farther afield.

Most high-quality American ciders come in 22-ounce bottles, like beers. But a 750-millliliter cider likely will entice more wine drinkers, says Dennett, who expanded Beerworks in June to Jacksonville, where customers also can choose from several Southern Oregon wines by the glass. Beerworks is one of the locations that Eden Valley planned to approach with Pear House, says Campanella.

“We’d love to see it in restaurants,” she says, explaining that 375-milliliter bottles should promote the cider’s sales in food service.

The majority of Pear House purchases will be from the EdenVale tasting room and for special events on the property, says Campanella. Priced at $14 per half bottle and $28 for the standard 750 milliliters, the cider constitutes the quickest release on the estate, where red wines age as long as eight years, she says.

The Pear House project bore yet another kind of fruit. Carbonating cider coaxed Campanella to create EdenVale’s first sparkling wines—white and rosé blends anticipated for release next summer.

“It’s an exciting time to get into cider,” says the winemaker.

This article reprinted from the Fall Winter 2016 issue of Southern Oregon Wine Scene.