Pioneer Profiles – September 2022

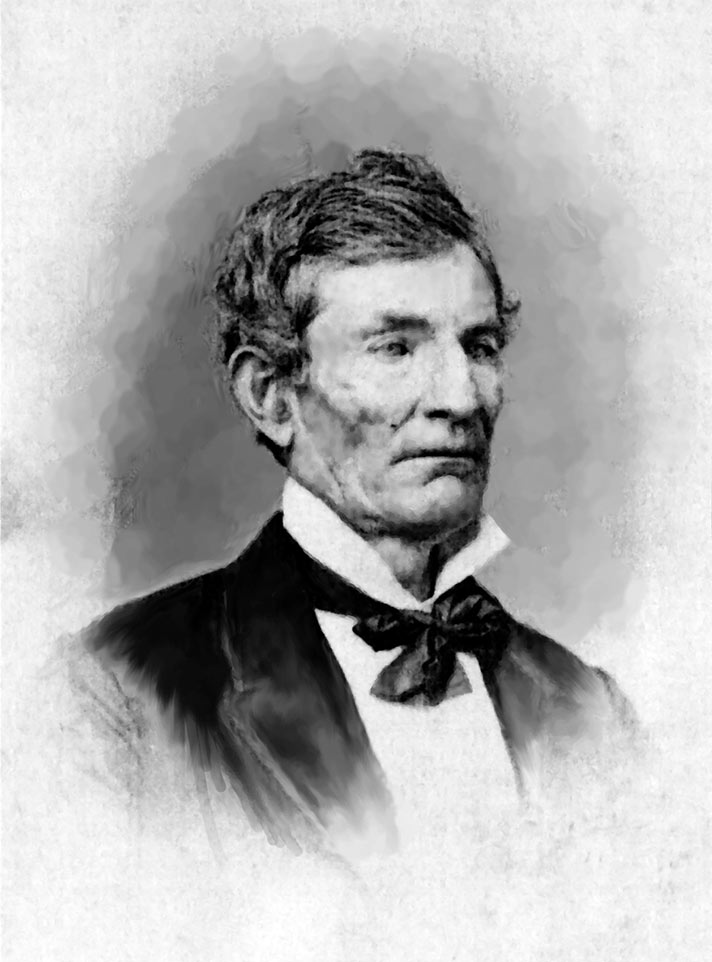

Last month we introduced you to William T’Vault, or Tevault, or Teevault—depending on the when and where—inasmuch as this pioneer regularly reinvented himself. We traced him through an early legal career; a marriage to the “granddaughter” of Daniel Boone; a jail break following charges of murder and rape; an arduous trek across the Oregon Trail; resumption of a law career in Oregon City; increased involvement in politics, and a short-lived tenure as a newspaper editor. A religious conversion wherein he confessed to being “an adulterer, a gambler, a hard drinker, and a scoundrel” also proved to be short-lived when opportunities for new versions of himself soon appeared.

In 1850, when Oregon’s Territorial Governor, General Lane, decided to try his hand at mining for gold in northern California, he invited T’Vault to join the venture. A party of 15 white men and 14 Klickkitat Indians headed south to the Klamath River. A temporary treaty enroute with the Takelmas proved successful; the gold panning less so and the party returned to Oregon City.

Having led an ill-fated wagon train party across the Oregon Trail and traveled to Yreka a few times, T’Vault now touted himself as an experienced guide. The “experienced” part, however, reflected more ego than knowledge. In 1851, he was hired by Major Phil Kearney to move his troops of mounted riflemen from Fort Vancouver to Missouri by way of Fort Benicia in California. The treaty with the Takelmas had not held, and the troops found themselves in an unsuccessful four-day battle near what is now Shady Cove. Intervention by territorial Governor Gaines allowed Kearney’s troops to proceed and saved T’Vault’s bacon. He parted ways with the troops at Fort Benecia and returned to Oregon City.

In August of that same year, T’Vault’s services as “a good, practical mountaineer and Indian fighter” were hired to find a route (if one existed) for a road from Port Orford up the Rogue River Canyon where it could link to the California-Oregon trail and access the northern California gold mines. In the early fall he set out from Port Orford with a company of 23 men and a train of pack animals.

For the first time T’Vault was relying on his own resources. He assumed that the distance from the ocean to the Rogue Valley would only be about 40 miles and struck out in what proved to be a senseless manner, paying no attention to mountain ridges and the natural direction of streams. He would lead his men to a mountain top, plunge over the crest, down the slope to the bottom and then back up the next elevation, slashing through heavy underbrush, but with no consistent pattern. He proved unable to identify any of the mountains or prominent landmarks.

After eight days, rations were running out and T’Vault’s ineptitude was well apparent. Despite his offer of $50 to every man who would stay with the party, only 10 chose to do so. The remaining individuals, though weakened by hunger, soldiered on.

Let’s just say that the rest of the trip did not go well. Specific details vary by individual account.

In brief, the men followed an Indian trail through rough, mountainous country with T’Vault anticipating it would lead them to the old Hudson Bay Company fort and trading post on the Umpqua River. However, their sense of direction was inaccurate. Weak, starving, with clothes in tatters, they eventually found a branch of the Coquille River—along with Coquille Indians.

Too weak to travel much further, T’Vault’s party decided to return to the coast. They hired the Coquille as guides to take them downstream in their canoes—paying for their services with many of their remaining clothes. The Coquille showed no significant signs of hostility until the party was within two miles of the ocean. At that point, their Coquille guides refused to go any further. T’Vault, overcome by fatigue and hunger and induced by an onshore display of salmon at a large Indian “rancheria,” persuaded the majority of the party to put into shore.

Big mistake! T’Vault’s company soon found its beached canoes surrounded by 150 hostile Coquille. Five men were killed; three escaped. T’Vault and one of his men, Gilbert Brush, managed to claim a canoe and paddle to the opposite shore, unnoticed in the chaos of battle. Stripping off their wet outer clothes so they could move more freely, they ran into the thick undergrowth where Brush, suffering a severe head wound, lapsed into unconsciousness.

T’Vault, seeking to save his own hide, abandoned Brush, and headed for the coast. An encounter with another group of Indians relieved him of his underwear. T’Vault arrived back in Port Orford wearing only his birthday suit. Brush managed to stagger in three days later.

In an account to the Indian agent and local newspapers, T’Vault left out a few facts and described himself mainly in heroic terms. He even wrote to General Lane describing his prospects as “in the ascendency.” His surviving companions were less charitable. Let’s just say that this adventure of T’Vault’s effectively ended his career as a guide. It may have also had something to do with his decision to move his family to Southern Oregon.

In one of his reports T’Vault had noted that he had discovered “the most fertile valley on that river that mortal has ever been permitted to look upon. Ash, maple, and other timber familiar to the Ohio and Wabash bottoms with the wild cucumber vine is to be found there in its most flourishing state.” He was “of opinion that corn could be raised there in great abundance.”

But, still certain that Port Orford would be the gateway to the mines in northern California, T’Vault planned to establish a general store and trading post there, and purchased merchandise and stock to outfit it. Then word reached him of the discovery of gold in the Jacksonville area. One direction was as good as another for T’Vault. Ever the opportunist, he canceled his orders for stock and supplies and headed for Rich Gulch.

T’Vault thought to again try his hand at mining. As he neared Jacksonville, he learned that nuggets had just been found in the area where Gold Hill would later be established. Stopping at a spring on the south bank of the Rogue River, he surveyed the clear bubbling water and the strip of green land nestled against the hills and decided that he had reached his destination. He proceeded to file a donation land claim for 210.7 acres and named it “Dardanelles.”

It was the spring of 1852.

Next Month: Southern Oregon and more reincarnations….

Pioneer Profiles is a project of Historic Jacksonville, Inc., a 501(c)(3) non-profit whose mission is to preserve Jacksonville’s Historic Landmark District by bringing it to life through programs and activities. Don’t miss our last summer “Walk through History” tours and Beekman Bank Museum “Behind the Counter” tours over Labor Day weekend. Then join us September 9th for more Haunted History tours and mark your calendar for September 17 and 18 and a full weekend of Victorian Fashion at the 1873 Beekman House Museum!

Follow Historic Jacksonville on Facebook (historicjville) and Instagram (historicjacksonville) and visit us at www.historicjacksonville.org for virtual tours, blogs, upcoming events, and more Jacksonville history.