Pioneer Profiles – June 2019

Part of being human is to identify things by naming them so that we can relate to them, personalize them, own them if you will. My parents named me Carolyn. To distinguish me from my mother, family members called me Lynn. To long-time friends, I’m Fox or Mac.

Place names also change over time. Perhaps named initially for a landmark, event, or person, memories fade; new events occur; a more recent person is honored.

Have you ever seen any daisies along Daisy Creek? That’s because there aren’t any. The original name of the creek was Dairy Creek. Are, or were, there any dairies along the creek? No. But there was a Dairy family, and that’s where this story really begins.

There, and with GOLD!

Like individuals from all over the world, a young family in Adams County, Illinois, heard the call of western gold. In the summer of 1851, Phillip and Cynthia Dairy packed up their two young children, Jacob and Edna, and headed across the plains, arriving safely in Oregon City before the first snowfall. Cynthia had become pregnant during the trek and in March of 1852 gave birth to their youngest son, Basil. Basil was less than two months hold when they headed south to Jacksonville in search of their first gold nugget.

The only way to make the trip was on horseback and for much of the way the route followed a creek bed. With the uncertain footage, a traveling party might typically cover 15 miles in three days. At some point, the horse Cynthia was riding slipped and fell, breaking her arm.

In the spring of 1852 Jacksonville was a new mining camp, less than six months old. Reminiscences of early Jacksonville describe it as an almost exclusively male community of homesick young men, who would loiter shyly about the homesteads of the few married couples in the valley, hoping for a few words of conversation with a real, live woman—or the opportunity to exchange some gold dust for a loaf of bread or a dried-apple pie baked by female hands.

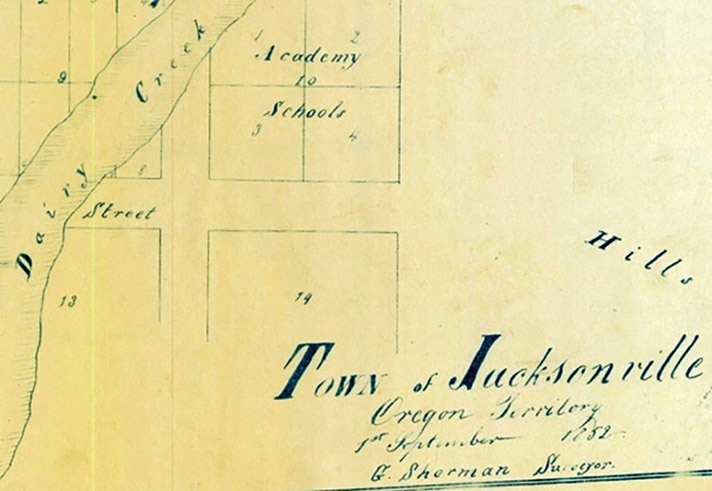

Picture a young, pale “madonna” with a broken arm riding into Jacksonville in May of 1852. She would have been an instant celebrity in the mining camp, as would her six-year-old son, her three-year-old daughter, and infant son Basil—the first white baby to reside in the Rogue Valley and the only white baby for fifty or more miles in any direction. This celebrity would have been reason enough to name a landmark after the young family. And sure enough, the name “Dairy Creek” appeared on the first map of Jacksonville, less than four months after their arrival.

Unfortunately, Cynthia died less than a year and a half later from “consumption”—tuberculosis—leaving Phillip with three small children. According to Jacksonville’s cemetery records, she was originally buried in the “old cemetery” and later reinterred in the City section of the town’s 1859 Pioneer Cemetery.

After Cynthia’s death, Philip apparently gave up his search for gold and ran a boarding house in Jacksonville called Miner’s Home. There’s no way of knowing if it was on Dairy Creek, but a list of unpaid I.O.U.s reads like a Who’s Who of the early settlement.

In the spring of 1854, tragedy again struck the Dairy family. Phillip became unexpectedly ill and died on March 29th in Salem, apparently while operating a pack train. Ten days earlier he had written his last will and testament, claiming Marion County as his residence and appointing Towner Savage, a farmer near Salem, as executor of his will and guardian of his children. Phillip is buried in the I.O.O.F. section of the Salem Pioneer Cemetery.

Although, Philip’s last will and testament had decreed that his three children were to remain with Towner Savage, only the eldest son, Jacob, did. Edna, the Dairy’s only daughter, had been adopted by the family of the Rev. Obed Dickinson and took their family name as her own.

During Cynthia’s illness, the William Wright family had stepped in to care for Cynthia and infant Basil. Following her death, they continued to foster him, and he remained with the Wrights, leading a quiet life until adulthood. He then left southern Oregon for the Oregon-Idaho border, never marrying and remaining there until his death in 1918.

The Wright homestead was five miles from Jacksonville, on what would become Kings Highway in the future Medford. With the death of Philip Dairy, less than two years after the Dairy family arrived in Jacksonville, no Dairys remained in town. The only remaining evidence of their brief celebrity was Cynthia’s original unmarked grave and a word on a map naming an insignificant tributary.

Jackson County Commissioners’ Journals, mining and property deed records, water rights records and surveyor’s notes at the Jackson County Surveyor’s office include no mention of the creek under any name, or even any reference to the watercourse. No water right was ever claimed on the creek; no surveyor or property deed used it as a landmark. The creek was apparently just not sufficiently significant to be discussed by anyone not living on it.

Then on the 1871 map of Jacksonville, prepared by the Rogue Valley Abstract and Title Company, the name of the creek, first written as “Dairy,” was “corrected” to “Daisy.” By the time someone’s whim “corrected” the map, the Dairy family was long gone and forgotten. We can only speculate that that person, reasoning that there were no dairies on Dairy Creek, assumed the name was a typographical error—not considering that there weren’t any daisies on the creek either.

No mention of the creek even appeared in Rogue Valley newspapers until 1881, when Jacksonville’s Trustees decided to build a $45 footbridge over it, briefly making the creek a matter of record. Referred to as the “Daisy Creek Bridge” by both the Trustees and the Oregon Sentinel, the bridge became the landmark that the seasonal tributary never was and cemented the “corrected” name in the public consciousness.

“Daisy Creek” has been the name used for the creek ever since.

Pioneer Profiles is a project of Historic Jacksonville, Inc. Visit us at www.historicjacksonville.org and follow us on Facebook (historicjville) for a full summer of activities and more Jacksonville history.