Pioneer Profiles – September 2020

As schools are struggling to find ways to accommodate students during the current COVID-19 pandemic, September seems an opportune time to look at the schooling available to the children of Jacksonville’s early settlers.

While older children arriving in the Oregon Territory in the mid-19th Century might have attended school in the towns or cities they originally called home, most of the youngest arrivals would have been “home schooled,” learning their ABCs while jolting across the plains in wagon trains bound for Oregon. Any schooling beyond that would have depended on their parents’ education levels and what time could be spared from all the chores that came with making a new life. Those hungry for knowledge might be self-educated, devouring any books available.

The first successful school in the Rogue Valley was started in 1853 by 16-year-old Mary Hoffman, daughter of soon-to-become prominent Jacksonville settler, Squire William Hoffman. It was a subscription school where parents paid “by the scholar” for the number of days their child attended. (With the need for farm labor, subscription schools were often open only during the winter.) The school was a one-room cabin near what is now Talent, consisting of a dirt floor, rough wood slab benches, a fireplace, and about twenty pupils. The students brought whatever books they could find to use as texts. In the fall of 1854, Mary’s school attracted about forty students and was relocated to an old stage stop about a mile from Phoenix. The students paid tuition in produce, poultry, and livestock.

One room schoolhouses were the norm. Students typically learned reading, writing, grammar, rhetoric, arithmetic, geography, and history, and one teacher taught all grades and all subjects. The teacher would call a group of students to the front of the classroom for their lesson, while other grades worked at their seats. Sometimes older kids helped teach the younger pupils. A school day might begin at 9 a.m. and end at 2 or 4p.m. with a one-hour “nooner” for lunch and recess.

In the spring of 1855, Jacksonville raised $600 in taxes to construct a schoolhouse on North Oregon Street—currently attributed to the southern portion of the house located at 560. An 1864 town map shows a small “District School” located in that vicinity on property owned by James Clugage, one of the town’s founders. By 1866, the students were overflowing the original structure and a new tax was levied to purchase or lease a new schoolhouse on Bigham Knoll.

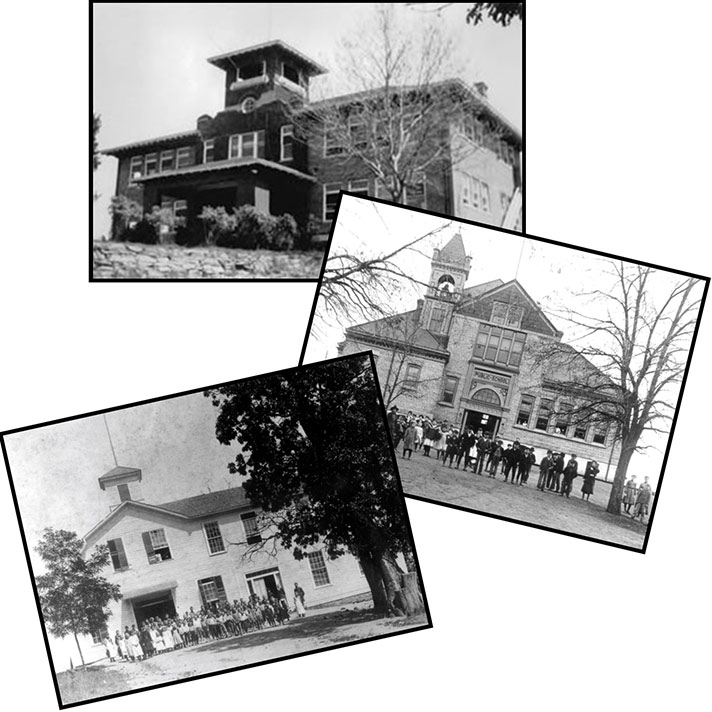

One year later, the seven-acre campus at the end of East E Street in Jacksonville known as Bigham Knoll became home to Jackson County School District #1 for the next 100 years. When the school district directors acquired this property, they converted an existing two room house into a school building until local builders could erect a new school. A two-story frame and “weather boarded” schoolhouse was soon constructed. It served three generations of Jacksonville students.

Students paid $5 per quarter in tuition until 1875, when the school levy was increased enough to do away with the tuition tax. A year later, the increased school enrollment necessitated enlargement of the building and an addition was completed “sufficiently large to accommodate all the pupils of the district.”

Teachers were expected to lead exemplary lives and to be regular church goers. Female teachers were dismissed if they chose to marry. Indulging in an intoxicating drink or a game of chance was cause for immediate dismissal. Teachers were also required to provide coal for heating and water for drinking, to fill and clean the kerosene lamps, and to provide the students with sharpened quills for writing. After five years, a teacher might receive a 25¢ raise. Teacher turnover was high, tenure was unheard of, and few teachers stayed more than a year or two.

One instructor of note was Professor John W. Merritt, teacher and principal from 1875 to1885. He demanded high standards of scholarship and behavior, and in a few years under his directorship, District #1 became the top-ranking school in the state.

Then on January 25, 1903, Jacksonville’s 36-year-old wooden schoolhouse burned. Within a month the School Board made plans to raise a new fireproof brick building. S. Snook, contractor “for so many of the new school buildings of the better class in Oregon,” erected a new five-room brick structure. However, the best laid plans…. Almost four years later this “fire proof” brick structure was totally destroyed by fire on December 13, 1906.

Even though the building was not fully paid for, voters quickly approved a bond measure for another school. The new fireproof brick building, completed in 1908, was acclaimed one of the best-appointed schoolhouses in the state with six classrooms, a large assembly room with a large stage fitted with electric footlights, and a steam heating plant.

However, public schools were not the only option available to Jacksonville students in the late 1800s. The original public schools were “grammar schools,” offering at most an eighth-grade education. Some families wanted access to “higher learning”; others sought education for their children more in keeping with their culture or values.

In June of 1862 Jane McCully opened “Mrs. McCully’s Seminary,” the town’s first school for girls. Jane was a trained teacher, and her seminary was so popular that by the end of the year she converted her former home at the corner of 5th and California streets into classrooms. Even after the public school no longer charged tuition, Jane provided advanced education for both girls and boys. She was the only teacher the children of many of Jacksonville’s prominent families ever knew.

Another private school was St. Mary’s School, once located in the cul-de-sac off E. California Street now known as Beekman Square. Established in 1865 by three members of the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, it operated as a 12-year boarding and day school for the daughters of the more well-to-do pioneer families. It graduated its first student in 1871.

Students were charged $40 for board and tuition for an 11-week term, with four terms offered each year. Bed and bedding were an additional $4. Girls wishing to study drawing or painting paid an extra $8; piano students paid $15. A “select day school” was also offered with tuition of $6 for primary grades, $8 for juniors, and $10 for seniors.

Before the Sisters of the Holy Name opened St. Mary’s, they briefly operated St. Joseph’s School for Boys in the building at 310 North 5th Street also known as the Catholic Academy. The Sisters had been brought to Jacksonville by Rev. Francis Xavier Blanchet, who for many years served as the parish priest of St. Joseph’s Catholic Church. The school was short lived, before being replaced by St. Mary’s.

However, since St. Mary’s only served girls, Father Blanchet also pursued the education of Catholic boys, offering classes in his home—St. Joseph’s Catholic Rectory at the corner of North 4th and C streets.

An early structure at 360 S. Oregon Street, home to German-born William Kreuzer, grocer and owner of the City Bakery and Saloon, also reportedly doubled as a “German school.” It served the children of Jacksonville’s German-speaking population—about one-third of the town’s early settlers.

Even with the steadily increasing number of educational opportunities available to early students, the quality and availability of education varied by socioeconomics, location, and ethnicity—not unlike today. Children on homesteads would most likely be home schooled when/if time away from farm work allowed. In town, children provided needed labor and income for families. Few students advanced beyond grade school. In 1900, only 11 percent of all children between ages 14 and 17 were enrolled in high school; even fewer graduated.

So this might be a good time to reflect on the educational options available today—or just the fact that there are options. While we certainly look forward to the time when our schools can reopen, we are fortunate to have the opportunities—and choices—that we do.

Featured image: The last 3 schools on Bigham Knoll.

Pioneer Profiles is a project of Historic Jacksonville, Inc. Given the need to cancel all events this summer, we’re also providing on-line learning opportunities at www.historicjacksonville.org. Join us for two virtual tours—”Walk through History” with weekly stops at sites in Jacksonville’s National Historic Landmark District; and “Mrs. Beekman Invites You to Call…,” an opportunity to tour the 1863 Beekman House Museum, home to Jacksonville’s wealthiest and most prominent pioneer family, with Mrs. Julia Beekman as your tour guide.