Pioneer Profiles – March 2021

Jacksonville is “celebrating the Shamrock” this month so Historic Jacksonville, Inc. is going Irish by highlighting one of our early settlers, Patrick J. Ryan.

In the 1840s, over half of the immigrants coming to America were Irish. Patrick J. Ryan, a 13-year-old native of County Tipperary, Ireland, was one of them. He arrived in the U.S. in 1842. Ten years later, he joined the westward immigration, crossing the plains and reaching Southern Oregon in the fall of 1852.

Ryan began his career in Jacksonville as a clerk, but a year later he had purchased half ownership of the Palmetto Bowling Saloon, marking the dawning of a career as one of the town’s earliest and longest-term commercial property investors. The Palmetto was soon renamed the New England Bowling Saloon and boasted quite an “assemblage of mirrors, tables, benches, lamps, decanters, and a stove.” However, Ryan’s career as saloon owner appears to have been short-lived since within the year the bowling saloon was under new ownership.

His interim activities are unknown, but according to his obituary, in 1856, Ryan’s “entire holdings were destroyed by fire.” That may have been an incentive for Ryan to subsequently specialize in “fire proof” brick buildings. That, and the fact that the seller of the lot he purchased at 175 E. California Street required that any building on that site be constructed of brick or stone. Ryan continued as a merchant, but he became one of early Jacksonville’s most prolific builders of “fire-proof” commercial structures.

In 1861 he constructed a one-story brick mercantile storehouse on his California Street property. As with most of Ryan’s buildings, space was rented out to various town merchants. Ryan himself was occupying the building when it burned in the fire of April 1873 that destroyed the entire block. He suffered one of that fire’s heaviest losses—$30,000 in merchandise and, of course, the building itself.

Despite his brick building being “fire proof,” Ryan had taken out fire insurance on both the building and on his “stock of dry goods, groceries, hardware, and merchandise.” Within a year, Ryan was erecting a two-story brick mercantile warehouse on the foundation of his previous storehouse.

Months later, the building “continued heavenward” with a third story wooden “pent house” (later removed), making it the tallest building in Oregon. The Oregon Sentinel proclaimed it to be “as fine a building of the kind as there is in any town this size in the state.”

According to Fletcher Linn’s Memories, Ryan’s store was on the ground floor and his living quarters on the second floor. Who occupied the “penthouse” is unknown although we could make some guesses. Ryan occupied the second floor and used the ground floor as a general store well into the 1800s. Today the building houses the Jacksonville Inn and Restaurant.

Around 1861, Ryan also commissioned a two-story brick building across the street at 120 E. California, the second two-story brick building erected in Jacksonville. It is historically known as the Wade, Morgan & Co. building after one of its earliest tenants. Ryan resided in the building in the early 1870s, probably while his new warehouse across the street was under construction. By the end of the decade the Oregon Sentinel newspaper occupied the top floor and the ground floor had been converted to a saloon and remained such into the early 1900s.

By 1865 Ryan had also acquired ownership of the lot at 125 South 3rd Street and probably constructed the building South Stage Cellars now occupies. Commonly known as “Ryan’s Dwelling House,” there is no indication that Ryan actually “dwelled” here, but the term may refer to the use of the building as a hotel. It appears to have been such from 1868 to 1871, and again from 1873 to 1883. In other years it was a doctor’s office, a butcher shop, and an ice cream parlor.

Ryan had an interest in numerous other Jacksonville structures, both domestic and commercial. But apart from his business interests, little is known about him other than residents deeming him “a character.”

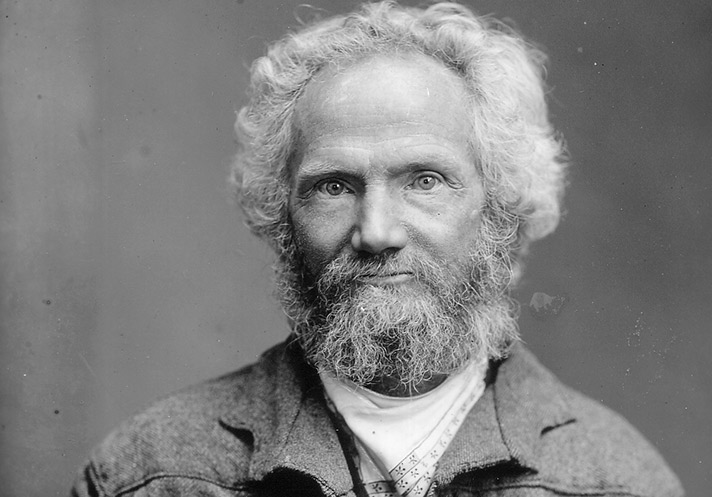

Memoirs written by members of Jacksonville’s “second generation” describe him as having “a plentiful supply of ‘bush’ kinked light red hair, quite long” and never seen wearing a hat. The writer doubted he even owned the latter.

Another recalls Ryan being “a great believer of taking sun baths, stitchless.” Apparently his favorite spots were a tree on the premises below the school grounds or on the roof of his brick buildings. Boys reported often seeing him “on a very hot summers day with an overcoat on, carrying a lighted lantern.” They would say, “Pat, what you dressed like that and got a lantern lighted for?” His reply was, “Did you ever hear of the man who got rich attending to his own business?”

Ryan was such a believer in sun baths that in 1881, when President Garfield clung to life for months after being shot in an assassination attempt, Ryan decided the doctors were hindering rather than helping his recovery. He wrote a letter to the President inviting him to southern Oregon where the sun baths were famous for their healing powers and were free of charge. He received no reply. Who knows if Garfield would have lived had he followed Ryan’s advice.

In 1862, Ryan married Elizabeth St. Clair Dill, a native of Indianapolis, Indiana, and eight years his junior. Better known as “Lizzie,” she might also be called a “character” inasmuch as she did not adhere to the norms for women of the day. In 1858, Lizzie was a candidate for Indiana State Librarian. She apparently was not elected since by 1859, at the age of 20, she was an “actress,” touring Indiana and “the West” giving poetic and dramatic readings. Perhaps that is when she initially met Ryan.

By 1860 she was publishing a newspaper, the Indianapolis Gazette, described as an eight-page “family newspaper devoted to literature and news—the useful and the beautiful.”

From 1862 to 1909, Ryan and Lizzie held extensive property in Jacksonville. The couple had one son, Luke, born in 1866. Luke became a relatively wealthy man when Ryan died in 1908. Shortly thereafter, Lizzie was judged insane. She died in 1913 in an asylum. Both are buried in the City section of Jacksonville’s Pioneer Cemetery.

Luke Ryan did not stay in Jacksonville. By 1920 he was the owner of a dry goods store in Medford, married, with two daughters and a son. Ten years later, Luke and his family were living in San Diego.

Although the family may have left the area, Patrick Ryan’s legacy remains in the various buildings he constructed or commissioned that highlight Jacksonville’s National Historic Landmark District.

Pioneer Profiles is a project of Historic Jacksonville, Inc., a non-profit whose mission is to preserve Jacksonville’s Historic Landmark District by bringing it to life through programs and activities. Join us for A Virtual Walk through Jacksonville—now a video as well as a blog! Follow us on Facebook (historicjville)and Instagram (historicjacksonville) and visit us at www.historicjacksonville.org for virtual tours, blogs, upcoming events, and more Jacksonville history.