Pioneer Profiles – February 2021

Many of Jacksonville’s early merchants were Jewish, fleeing wars and persecution in their homelands by immigrating to the United States. Most of the town’s Jewish merchants moved on to Medford, San Francisco, New York, and other cosmopolitan centers when the railroad bypassed Jacksonville in the 1880s in favor of the flat valley floor. They saw it as the end of local business endeavors. Customers could now acquire goods from San Francisco or Portland more cheaply. These merchants failed to recognize that the railroad also gave them easier access to supplies as well as access to a larger customer base since they could now ship their goods throughout the country. Three, however, stayed, living out their lives in Jacksonville and helping to shape the fabric of the town during the last half of the 19th Century. They were Morris Mensor, Gustav Karewski, and Max Müller. Müller, is the subject of this month’s Pioneer Profile.

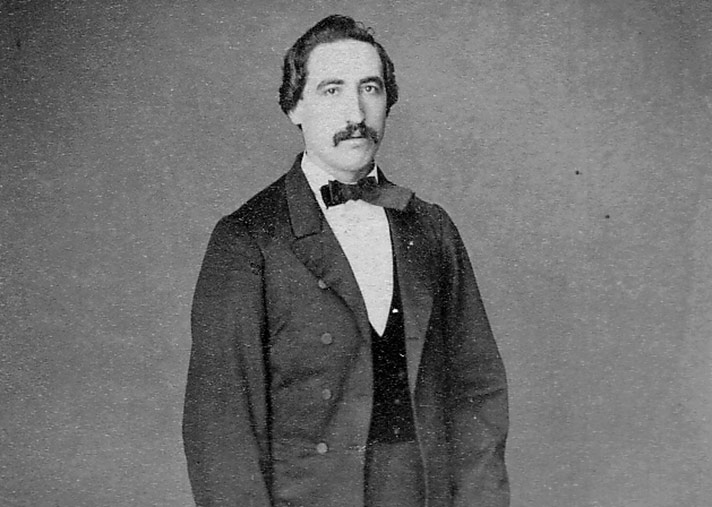

Müller, a native of Reckendorf, Bavaria, had immigrated to the U.S. in 1851. He apparently came on his own although he was only 15-years-old, but certainly had connections in the American German community. He had no difficulty finding work and for the next four years clerked in various general merchandise stores on the East Coast, gaining experience and becoming familiar with the English language.

By the time he turned 19, the lure of the West and its promise of adventure and fortune claimed Müller like so many before him. Securing passage on an old steamer, Uncle Sam, he arrived in Jacksonville by way of Nicaragua in 1855. A number of Jewish merchants were already well established in Jacksonville and Müller readily found employment.

Saving his earnings and desiring to be his own boss, Müller moved to Ashland in 1858 where he operated his own saloon. Saloon keeping came with its own challenges. An 1860 court record charged him with keeping his liquor business open on Sunday, a violation of the 1855 “Act to Prevent Sabbath Breaking,” that provided for a fine for anyone keeping “a secular business open on the Lord’s day.” However, the law appears to have been only whimsically enforced because Saturday and Sunday were also the major local shopping days. At any rate, Müller was found not guilty and the case was dismissed.

Legal issues may have provided an incentive for Müller to leave Ashland, and Jacksonville had previously captured his affection. In 1862 he returned to town, leasing what had been the Brunner Brothers store and going into the dry goods business for himself. Four years later, he acquired a partner, Max Brentano, a partnership that was to last for two decades. Within three years they were some of the wealthiest merchants in town with the 1869 tax rolls showing declared personal property of $25,850.

That same year Müller & Brentano relocated their “groceries, candies, nuts, and stationery” store to the corner of Oregon and California Street. Their store also became known as the “post office store” after 1870. In that year, Max Müller was appointed postmaster of Jacksonville. As well as an honor, this was a good business opportunity. For the next 18 years Müller served as postmaster and the “post office” was located wherever his business was. After the fire of 1874, Müller & Brentano moved to 125 W. California, currently occupied by the J’ville Tavern. This location became the “new” Post Office Store until 1888. After that it became “Max Müller & Co., Jacksonville, Or., the leading dealers in Gents Furnishing Goods.”

Soon after returning to Jacksonville, Müller became active in local politics. Having lived in a Europe that denied Jews the right to hold office or even to vote, he freely gave of his time. He was elected a town Trustee in 1863, serving as President of the Board. He was then elected City Treasurer in 1864, 1867, and 1868. In 1868, he was also elected Jackson Country Treasurer. He was elected County Clerk in 1890 and re-elected in 1892 and 1894. He was again elected County Treasurer in 1900 and 1902. None of his elections were “sure things” and he received pushback from some local newspapers, citing his membership in the “tribe of Levi” and his reading of the court Journal “in that rich German dialect.” The bigoted attacks proved unsuccessful, and they may even have helped elect him.

As active as he was in business and politics, Müller was even more so when it came to local fraternal organizations. For nearly 32 years he served as Secretary of Warren Lodge No. 10 of the Free and Accepted Masons. He was Recording Secretary of Jacksonville’s Stamm No. 148 of the Improved Order of Redmen. He was also Secretary of Oregon Chapter No. 4 of the Royal Arch Masons and a financial backer of the Banner Lodge of the Ancient Order of United Workmen.

Müller also contributed generously to town affairs. He donated to Fourth of July celebrations and other community events. When St. Andrews Methodist-Episcopal church was remodeled, he gave nails for the new fence around the property. After a particularly heavy snowfall, Müller supplied salaries to a working crew who cleared sidewalks and made paths across town streets. In 1864, he petitioned the town Trustees to allow him and a fellow merchant to construct stone crosswalks across the streets. And he regularly registered in the town military rolls although he was never called into service.

His energy and business interests even extended to being an insurance adjuster, real estate agent, estate executor, trustee, and ticket agent for various local theatrical productions. He also staked out at least two mining claims although he is not known to have worked them.

In 1887, Müller constructed the elegant Italianate style Victorian house on E. California to accommodate his growing family. The same year that Müller had returned to Jacksonville, he had married Louisa Hesse, also a native of Germany. Her uncle, William Hesse, had accumulated a fortune after coming to Southern Oregon from Dresden, Germany, and encouraged Louisa’s family to immigrate as well. Louisa was an attractive young lady of some means so Müller must have had considerable charm for her to accept his proposal.

The couple had seven children, two of whom died in infancy. Louisa was not Jewish, and the children were not raised in the Jewish faith. It is not known whether Müller converted to Christianity as part of assimilating into his adopted homeland. However, the joint headstone for Max and Luisa does read “Asleep in Jesus.”

Müller died in 1902 following a paralytic stroke shortly after again winning the race for Jackson County Treasurer. Louisa passed away in 1924. The couple is buried in the Masonic section of Jacksonville’s Historic Cemetery.

Pioneer Profiles is a project of Historic Jacksonville, Inc., a non-profit whose mission is to preserve Jacksonville’s Historic Landmark District by bringing it to life through programs and activities. Join us for A Virtual Walk through Jacksonville—now a video as well as a blog! Follow us on Facebook (historicjville)and Instagram (historicjacksonville) and visit us at www.historicjacksonville.org for virtual tours, blogs, upcoming events, and more Jacksonville history.