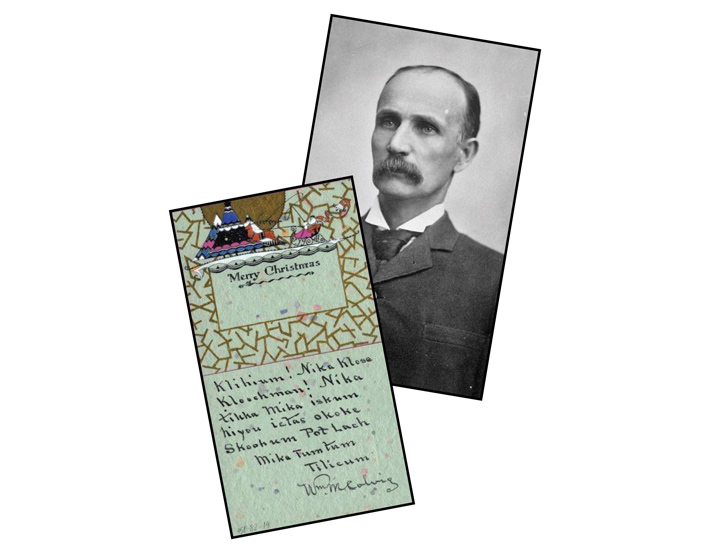

Pioneer Profiles – December 2018/January 2019

William Mason Covig’s Christmas greeting is written in Chinook, the “trading language” used between immigrants and the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest until around 1900. Colvig professed to have been more fluent in Chinook, the language of his childhood playmates, than in his native English. Born in Missouri in 1845 to a family of French descent, a six-year-old Colvig had been taught by his mother to read and write English while jolting across the plains in a wagon train bound for Oregon.

Colvig grew up in the Umpqua Valley near Canyonville where his father farmed, practiced as a doctor, and ran a drugstore. The family’s Oregon land grant encompassed an Indian village, and the native children became Colvig’s playmates. In addition to helping him learn to speak accentless Chinook, Colvig said his Indian playmates helped him to appreciate the beauties of the Oregon country.

Life in Canyonville provided Colvig with a collection of stories that spiced his public speeches in later years. In one he recalled that as a boy he wore buckskin britches. “You couldn’t wear them out. When they were outgrown, they went on down the line to the next boy in size. If there was any special reason to have them look clean, then Mother would send us down to the riverbank where we had a kind of an otter slide in the sand. We would sit down and slide and then lie down and slide until they were clean fore and aft.”

Colvig attended school for a year or two, but he was mostly self-educated. He hungered for knowledge, was an avid student of history and Shakespeare among other things and was a serious scholar.

Like many young men, he also had a thirst for travel. He saw the outbreak of the Civil War as an opportunity to satisfy that ambition and what he saw as his patriotic duty. As soon as he turned 17, he enlisted in Company C of the volunteer 1st Oregon Calvary. But instead of seeing fighting, his company remained in the West building Fort Klamath and mapping routes east of the Cascades.

While locating a road between Jackson and Klamath counties, his company came across Crater Lake, which they named Lake Mystic on their maps. Colvig, the company clerk, drew a crude map of the area, the first ever made, and the map was sent to Washington, D.C. for copying.

Mustered out of the army in 1866, Colvig was still eager to see other parts of the country. He left Portland for San Francisco, then traveled via tramp steamer to New York by way of Panama and Cuba where he was robbed of $481. Arriving in New York with only $1.75 to his name, he headed for West Virginia where he had relatives.

After borrowing $50 from an uncle, he traveled to Ohio, Illinois and Missouri, working at various times as an oil mine driller and pump operator, company store manager, and hemp plantation foreman. He studied law in Illinois, taught first grade for 18 months, then became a map worker in Ohio. He seemed to want to try his hand at everything and apparently did so with great enthusiasm. The knowledge he gained of people and vocations was put to good use in Colvig’s later years dealing with the public.

A job with Lakeside Publishing Company in Chicago took Colvig to Minnesota and Iowa where he wrote histories of those states. Then in 1875 the company sent him to California to be General Manager of the Pacific History Company. He arrived in San Francisco just in time to see the company go bankrupt.

After a 13-year absence he returned to Oregon to spend some time with his parents. They were now living on a farm in Rock Point between the towns of Rogue River and Gold Hill. Colvig relished being reunited with family. It appears he also relished making a new acquaintance.

Just three miles down the Rogue River was “Fort Birdseye,” home to the pioneer Birdseye family and their daughter Adelaide. Colvig began seriously courting her. It appears, however, that either “Addie” wasn’t ready for marriage or her mother disapproved of someone she couldn’t intimidate. Colvig headed back to California and resumed writing histories for a San Francisco publishing company.

But after a two-year absence, Colvig took matters into his own hands. He returned to Oregon and proposed to Addie. Addie’s mother even reluctantly agreed to the marriage, and the wedding took place at Fort Birdseye on June 8, 1879. The groom was 34, his bride was 23.

Colvig took over the Birdseye ranch and ran it for several years. He also began practicing law. Around 1882 he was elected Jackson County School Superintendent, serving two terms in that capacity. After Colvig became a county official, the family moved to Jacksonville.

His stint as School Superintendent was followed by Colvig’s election as District Attorney for the 1st Judicial District, a territory that included Jackson, Josephine, Klamath and Lake counties. Despite receiving a sizable majority of the votes, Colvig’s election was initially clouded by the incumbent, T.B. Kent, charging that Colvig forfeited the election by being “negligent” in claiming the seat the day after the Governor proclaimed Colvig the winner. Kent sued and took his lawsuit all the way to the State Supreme Court where the judges dismissed it, noting there was nothing in the law that limited the “window” for Colvig’s claiming the seat. There was a certain irony in Kent’s lawsuit, given that Colvig had supported Kent’s previous campaigns.

Only after this first election did Colvig take the bar exam, perhaps a way of “cementing” his position.

Colvig was elected to two more terms as District Attorney before retiring to private law practice in Jacksonville. During his time as District Attorney, he tried 182 cases and obtained 142 convictions. Local newspapers described District Attorney Colvig as doing his duty “without fear or favor” and proclaimed him “head and shoulders above” any prosecuting attorney they ever knew.

Next time: Private Practice, Public Orator

MARK YOUR CALENDARS for Secrets & Mysteries of the Beekman Bank on January 3, 4 and 5; a new season of “Pioneer History in Story & Song” featuring Northwest Troubadour David Gordon on each 2nd Sunday from January through April; and the return of Beekman 1932 Living History on each 4th Saturday from February through May.