The Peter Britt Gardens have become the newest Jacksonville landmark to be recognized on the National Register of Historic Places. Home to Swiss-American entrepreneur Peter Britt and his family from 1852 to 1959, the designation encompasses 4.7 acres that fronts on First Street between Highway 238 and Pine. It now houses the Britt Festival amphitheater and grounds, owned by Jackson County; and the popular Britt Gardens public park and one of the principal Jacksonville Woodlands trail heads, owned by the City of Jacksonville.

According to various accounts, Peter Britt arrived in Jacksonville in 1852 with a cart of photography equipment and five dollars in his pocket. Where gold seekers filed claims for mineral rights, Britt filed a donation land claim and built a dugout log cabin. After briefly trying gold mining, Britt and two fellow Swiss emigres ran a pack train between Jacksonville and Crescent City for the next three years. By 1856 Britt had accumulated a sufficient “grubstake” to buy a state-of-the-art camera, construct a second building on his property, and open “P. Britt’s Photograph and Daguerreotype Room.”

As the first photographer in Southern Oregon, people came from all over Southern Oregon and Northern California to have their portraits taken. Britt remained the most popular photographer in the region during his lifetime, photographing almost all the prominent citizens as well as farmers, miners, Chinese workers, and Native Americans. In the 1860s, he began pursuing landscape photography as well. He became the first person to successfully photograph Crater Lake, and the resulting photographs substantiated the proposal to make Crater Lake a national park in 1902. His Jacksonville photographs underwrote the establishment of Jacksonville’s Historic Landmark District in 1966.

However, Britt was much more than a photographer—he was an entrepreneur and capitalist. He was also an avid gardener, an agricultural innovator, and is considered the father of Southern Oregon’s commercial orchard, wine, and ornamental horticulture industries.

When he returned to his photography after his years of “mule skinning,” he also established a vineyard and planted orchards of pears and peaches to supplement his income. Raised in the grape districts of Switzerland, by 1861 he developed a 20-acre commercial orchard and expansive grape vineyards on property he purchased about a mile from Jacksonville. By the 1870s, he had experimented with over 200 varieties of American and European grapes and furnished vines for almost every vineyard in the Rogue Valley.

From these grapes, Britt made muscatel and zinfandel wines as well as a popular claret, marketed under his Valley View Vineyard label. By 1880 he was producing 1,000 to 3,000 gallons of wine per year, eventually filling orders from as far away as Wyoming.

Britt also produced and sold peaches, apples and pears. His orchards became a powerful economic driver in the early 1900s, a basis for the region’s “Orchard Boom” era.

He raised bees to improve pollination, and then sold the honey. He irrigated his property as early as 1855, installing an innovative irrigation system fed by a mile-long ditch and a system of underground pipes. He used smudging techniques to fight frost. He recorded weather observations in his personal diary, and when an official weather service was established within the Army Signal Corps in 1870, Britt served as a volunteer civilian observer.

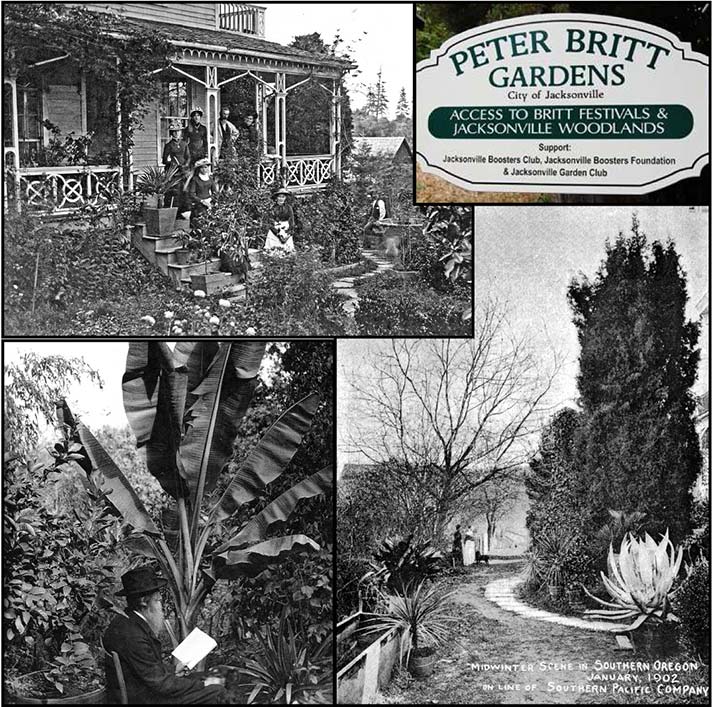

Britt’s interest in horticulture also extended to exotic plants. As early as 1859, he began keeping a list of plant specimens suitable for the region’s Mediterranean climate and surrounded his home with ornamental shrubs, exotic trees, and unusual botanical specimens. The property evolved into “Britt Park,” lavish Victorian botanical gardens eventually boasting nearly 300 varieties of cultivated plants. Britt Park became a feature of Northwest promotional publications in the late 1800s, and by the turn of the century had become a Pacific Northwest tourist destination.

Over time, Britt’s photography studio was converted to a home for his family as Britt continually enlarged it to accommodate a wife and three children. By 1882 the house was three-storied with 14 rooms and a large wine cellar and attached solarium. Although the house burned in 1960, the 1976 reconstruction of the foundation encompasses the footprint of Britt’s various expansions.

Britt died in 1905. Emil and Mollie (Amalia), his surviving children, occupied the property until his daughter Mollie’s death in 1954. In nominating the designated acreage, archaeologist Chelsea Rose cited remaining original features including the 1862 Giant Sequoia tree Britt planted when his son Emil was born; a 19th Century fountain dating from Britt Park’s peak tourist days; a 20th Century shed, and multiple archaeological sites.

The latter were uncovered in recent years as Britt Festivals has enhanced its music venue, and the City and the Jacksonville Boosters Club have undertaken restoration work on the gardens. To date, archaeological digs in conjunction with these projects have recovered over 5,000 artifacts associated with the property and identified Britt’s original log cabin, middens (garbage pits), barn, wine press, and the Old City Brewery. A 2008 cultural landscape survey provided a detailed history of the gardens and plantings and identified original trees, shrubs, and other plantings or their progeny.

The National Historic Landmark Designation considers Britt’s homestead a landmark of statewide significance, home to two generations for over 100 years and augmented by a robust documentary record of photographs, diaries, letters, and family heirlooms.

“Britt captured a changing region through his photographic images,

“After the death of their father, Emil and Mollie Britt dedicated much of their lives to his legacy, essentially living in a curated museum built on his life’s work. As such, they were active in the cultivation of the historical memory of early Jacksonville and its celebrated inhabitants. While documents support the extent of Britt’s notable achievements, he lived and worked in a community that was all but extinct by the early 20th century, and the enduring fascination of his story … may be in part due to the efforts of his children to preserve it.”