Pioneer Profiles – December 2019/January 2020

Most of Jacksonville’s original wooden buildings were destroyed in multiple fires, but a few remain. At least two of these landmarks were the work of master builder David Linn. One, the 1854 St. Andrews Methodist-Episcopal Church, was a product of his early Jacksonville career. The other, the 1881 Presbyterian Church, came towards career end. In between he built a fort, public and commercial buildings, houses, staircases, furniture, mining equipment, and coffins.

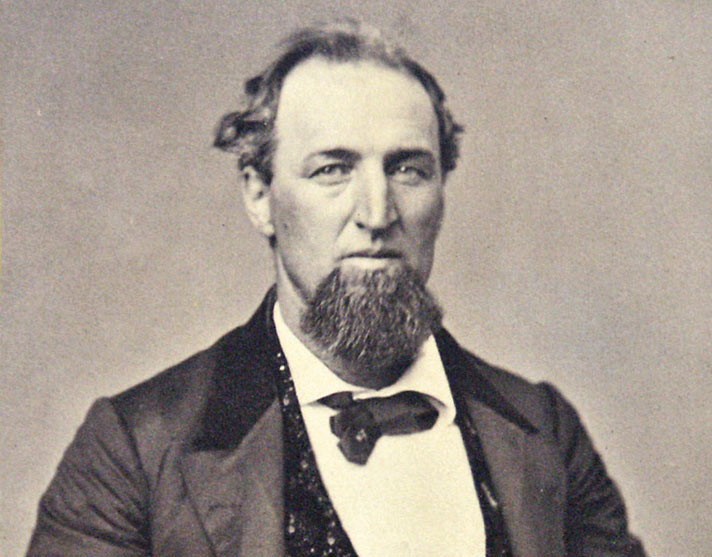

Linn was born October 28, 1826, in Guernsey County, Ohio, the oldest son of William and Margaret Linn. He received what was described as “a common education,” at the same time learning the carpenter’s trade. By age 14 Linn was self-supporting as a carpenter and cabinetmaker and at 25 he was actively engaged in the contracting and building business.

Like other young men of the time, Linn became fascinated by the stories of gold discoveries in the West. In the spring of 1851, he set off across the plains to Oregon, bringing with him all the tools he could pack for the six-month trek. He found employment in Oregon City but stayed only long enough to amass sufficient funds to head for the gold fields.

Hearing stories of fabulous strikes around Yreka, he decided to go there, packing his tools and supplies over the Siskiyous. A claim at Humbug Creek brought Linn considerable success, then he added to his fortune at Yreka Flats. When gold was discovered in Jacksonville in the winter of 1851-52, Linn became one of the original settlers, instrumental in transforming the mining camp of Table Rock into the town of Jacksonville.

Setting up a crude shop, he began making cradles and sluice boxes for the prospectors and sheds and cabins for the influx of settlers, merchants, and “hangers on” arriving daily in the new boom town. There was an instant demand for his products. People making the journey west had disposed of most of their possessions prior to departure so arrived with a bare minimum of necessities. They were eager to buy chairs, tables and beds.

Linn had some competition from a Mr. Burpee, but they soon realized there was more than enough business for both and formed the partnership of Burpee and Linn.

Around 1854, Linn decided to go out on his own. He purchased property at the corner of California and Oregon streets, the site of the present telephone exchange building, and constructed a two-story frame building. The ground floor served as display and sales rooms; the upper floor was for storage and finishing. Adjoining this was a large factory building.

According to David’s son, Fletcher, “In the factory were two circular saw tables, a head planer, jig saws, a turning lathe and work benches and tables. In the north end was a cabinet shop with tools, stove and glue pots. The boiler and the engine room were on the east side and adjoining the factory building. This structure contained the grind stones and equipment for repairs and upkeep. The plant kept a…crew of twelve to fifteen men…. They constructed many of the houses and stores in early Jacksonville.”

In 1856, Linn returned to Ohio where he purchased a small sawmill. When it arrived in Jacksonville two years later, after being shipped around Cape Horn to the mouth of the Umpqua River then hauled overland by ox-drawn wagon, it was probably the first steam-powered sawmill to arrive in Oregon.

In the meantime, Linn had purchased a small stand of pine trees about two miles out of town. Typically, building was done with materials available, pine was what was at hand, so Linn used pine almost exclusively in his various projects.

Most of Linn’s furniture was plain, suiting the rugged life of the period—kitchen tables, drop leaf dining room, tables, raw-hide bottom chairs and rockers, and spool beds. He also accepted more elaborate contract work. A pie safe in the kitchen of the 1873 Beekman House Museum is an example of his craftsmanship.

Linn was also the town coffin maker and most of the people buried in the Jacksonville cemetery in the late 1800s were laid to rest in his coffins. Made of pine, Linn’s coffins were covered in black velvet and trimmed with drop handles, thumb screws, and plates. The padded interior was lined with white muslin. He charged $10 to $20 for a child sized coffin and up to $50 for an adult.

In 1864, Linn accepted the sub-contract for building Fort Klamath, taking his sawmill to the site to square the logs for the buildings. As part of the job, he constructed the administrative buildings and barracks as well as homes for the married officers and men.

As the public became aware of the existence of Crater Lake, people wondered about its depth and source and were curious about Wizard Island. In 1869, Linn built a boat and, with the aid of Jacksonville friends, transported it in sections to Crater Lake. There they reassembled it, circled the lake, and explored the Wizard Island crater. Linn was probably among the first party other than Native Americans to take a boat ride on Crater Lake.

Linn was heavily involved in commercial and civic affairs as well. He had retained a holding in a ranch where he had grown hay upon his arrival in Southern Oregon, and subsequently developed an interest in orchards and other agricultural endeavors. He was a stockholder, company president, and business manager of the Jacksonville Milling and Mining Company, which developed and operated a large quartz mine about two miles out of Jacksonville.

Linn also served as Jackson County Treasurer. He had been appointed in 1854 and continued in that capacity for 14 years, making annual horseback trips to Salem to deliver $12,000 to $14,000 in gold and currency to the State Treasurer—a job that today would come with armored car and guards. He was a member of the Jacksonville City Council, served as Mayor, and was a school director for many years. He was also an active Mason.

In 1860, Linn had married Anna Sophia Hoffman, the third of six daughters born to Squire William and Caroline Hoffman, another prominent pioneer family. The Linns had seven children, three girls and four boys. Around 1883, Linn built a handsome two-story home for his family at the corner of North Oregon and F streets, across the road from his wife’s parents.

But then tragedies began striking the Linn family. William, the Linn’s oldest son, died of tuberculosis about the time their fine new home was finished. The entire town went into mourning.

Then in 1888, Linn’s furniture factory burned, destroying a neighboring home and most of Jacksonville’s remaining Chinatown. It appeared to be arson although no culprit was ever apprehended. A disheartened Linn elected not to rebuild but did continue his furniture business until selling it in 1903 after the railroad by-passed Jacksonville.

In 1900, Jim Linn, the family’s youngest son, succumbed to tuberculosis. His funeral was “one of the largest that Jacksonville ever witnessed.” In 1907, Anna Sophia also died of the disease. Neither Anna Sophia nor David lived to see a third son drown in the Willamette River.

David Linn died in 1911 at the age of 85 of “extreme old age.” According to the Jacksonville Post, “He was one of the hardy pioneers who helped open Oregon to settlement.” Historians cited Linn as “the founder of mechanized industry in Oregon.”

Linn himself might have preferred the tribute he received from his brother-in-law C.C. Beekman who wrote, “He was a fine example of the self-made man, honest and honorable in all his transactions and a man who enjoyed the confidence of all who knew him.”

Pioneer Profiles is a project of Historic Jacksonville, Inc., a non-profit whose mission is helping to preserve Jacksonville’s Historic Landmark District by bringing it to life through programs and activities. Visit us at www.historicjacksonville.org and follow us on Facebook (historicjville) for upcoming events and more Jacksonville history.