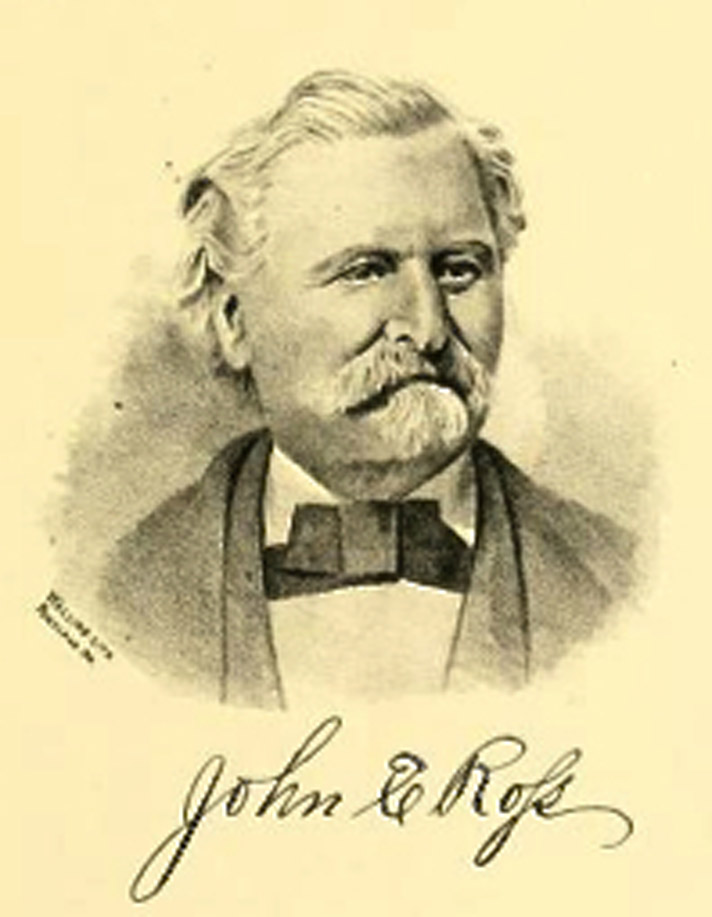

Pioneer Profiles – September 2017

When we left Colonel John England Ross in our August 2017 Pioneer Profile, he had barely avoided eating crow…literally. After finding gold near Sawyer’s Bar on the Klamath River in California in 1850, he had been wounded in a skirmish with Indians and had his horses stolen. By the time prospectors found Ross and his companions, the Ross party had been stranded without provisions for almost a month and were close to starvation. Ross had been carrying a crow he had captured for three days, anticipating he might have to eat it.

However, the prospectors, led by a man named Scott, provided a welcome meal instead. Full of wild game and gratitude, Ross told his rescuers about the rich gold strike they had made, but swore them to secrecy.

After a month of rest, recuperation, and restocking of animals and mining equipment, Ross returned to the site of his lucky strike only to find hundreds of miners crowding the area. Not surprisingly, Scott had been unable to keep a secret and Ross would not realize any return on his hardships.

An enterprising Ross hoped to recover some of his losses by packing supplies to the miners. He headed for the Sacramento Valley to acquire staples and utensils, leaving a friend, Hank Brown, with funds to buy a six-mule pack train. However, Brown lost the money to a card shark. Ross was indebted to Brown for saving his life, so rather than seeking revenge, Ross again returned to prospecting…with Brown as a partner. Working their way north, they arrived in what is now Yreka in the spring of 1851.

Shortly before their arrival, a horse had been stolen by several Indians. Ross offered to head a party to go after them. He found them in a small village about 60 miles to the east. During the ensuing fight, 15 Indians and four miners were killed. This was Ross’s first encounter with the Modocs. Among the “keepsakes” the miners acquired was a Modoc “souvenir”—the scalp of the chief of another tribe who had been a prominent peace advocate. Ross was soon to realize that the Modocs had no desire to settle hostilities and live in harmony with the settlers.

Ross and Brown apparently had sufficient mining success for them to buy a stock of merchandise and open a supply store. Brown ran the store while Ross looked for the “big one” that would make them rich. But Ross soon tired of limited success and the constant threats from the Rogue Indians. Within a month he gave away his mining equipment, left Brown to run the store, and moved back to the Willamette Valley where he took out a donation land claim.

Ross was ready to settle down. But when James Clugage and Ross’s old partner, James Pool, discovered gold on Jackson Creek, Ross saw another opportunity. He sold his land claim, bought a herd of beef cattle, drove them to what was to become Jacksonville, and went back into the butchering business. Michael Hanley, whom he had met in Chicago years before, became his partner.

With the influx of miners and settlers, Indian tribes became more hostile and aggressive. Even in what was rapidly becoming a settlement of several hundred inhabitants, the threat of attack was ever present.

In late spring of 1852, shortly after his arrival in Jacksonville, Ross somehow became aware that an Indian attack was imminent. As reported by Jane McCully in an 1890 memorial to Ross that she prepared for the Southern Oregon Pioneer Society, “[Ross] ran from cabin to tents, his clear loud voice ringing on the midnight air, ‘Indians, Indians! We are surrounded by Indians! Boys, get guns, get clubs, get axes, get anything you can lay hands on, and defend yourselves! Keep cool boys, and keep out of sight.’ He then gave two or three of his Indian yells, of which he was a noted expert, and called to the Indians in jargon, ‘Charco, charco, Nika Tika, Mem-a-loose Siwash!’” which can be loosely translated as “Come on, come on, if you want to be killed!”

This event was McCully’s first encounter with Ross. She continued to describe the scene. “The hills seemed swarming with murderous yelling fiends. That midnight call to arms pierced every heart. Women gathered their babes to their bosoms, and prayed their shortest prayer…. All the rest of that night of terror, the boys fired their guns at intervals.” The shooting and yelling proved effective and the warriors departed before dawn.

On other occasions, Ross was said to have ventured out alone at night “to the unprotected settlements to gather the sick and helpless and conduct them over the trackless wilds at midnight to places of safety” at a time “when every waving bush took the shape of a Painted Warrior.”

By mid-1852, the tide of emigrants had turned into a flood. Larger wagon trains, well-equipped and strongly armed, experienced few problems with Indians apart from livestock theft and pilfering of supplies on the now well-traveled Oregon Trail.

However, the Applegate Trail or Southern Route proved a different matter. The pass was often the scene of ambush and murder. Travelers had to use extreme care since the Indians readily attacked even troops of heavily armed volunteers sent to convoy wagon trains to safety. By fall of 1852 the Modocs had killed close to 100 men, women, and children on this Southern Route.

In September Ross organized a company of 22 men to serve as an escort party for wagon trains. They crossed the Cascades to the lake country where they joined forces with a group from Yreka. The volunteers were appalled by the evidence of carnage they discovered. Charred ruins of wagons lay along the trail. The bodies of murdered immigrants lay where they had fallen. The men buried their remains.

For several weeks the men attacked and routed Indians who were lying in wait for and besieging hapless wagon trains. But as winter approached, travel on the road ceased. By October, Ross was ready to return to Jacksonville.

He also had another incentive—an attractive young lady named Elizabeth Hopwood.

Next month’s final installment—marriage, peace talks, and government service.