Pioneer Profiles – August 2018

Early settlers recognized the Rogue Valley’s potential for grape and wine production long before the World of Wine, now the Oregon Wine Experience, began celebrating the award-winning varietals being produced in the region’s many micro-climes. As early as 1854, Peter Britt, the father of Southern Oregon’s wine industry, planted his first vineyards. Colonel J.N.T. Miller boasted 20 acres of vineyards and 20 varieties of grapes. William Bybee had five acres of mission grapes. Other settlers planted vineyards in Central Point, Phoenix, and Ashland.

In 1890 the editor of The Resources of Southern Oregon asserted that the region was specially adapted to the raising of grapes and it was destined to become the most profitable industry in Jackson County. Perhaps inspired by this assessment, a colony of French settlers from Tacoma, Washington, arrived in Jacksonville intent on “going into the grape and wine industry on a large scale” and sought “to secure all the available hill land in this vicinity.”

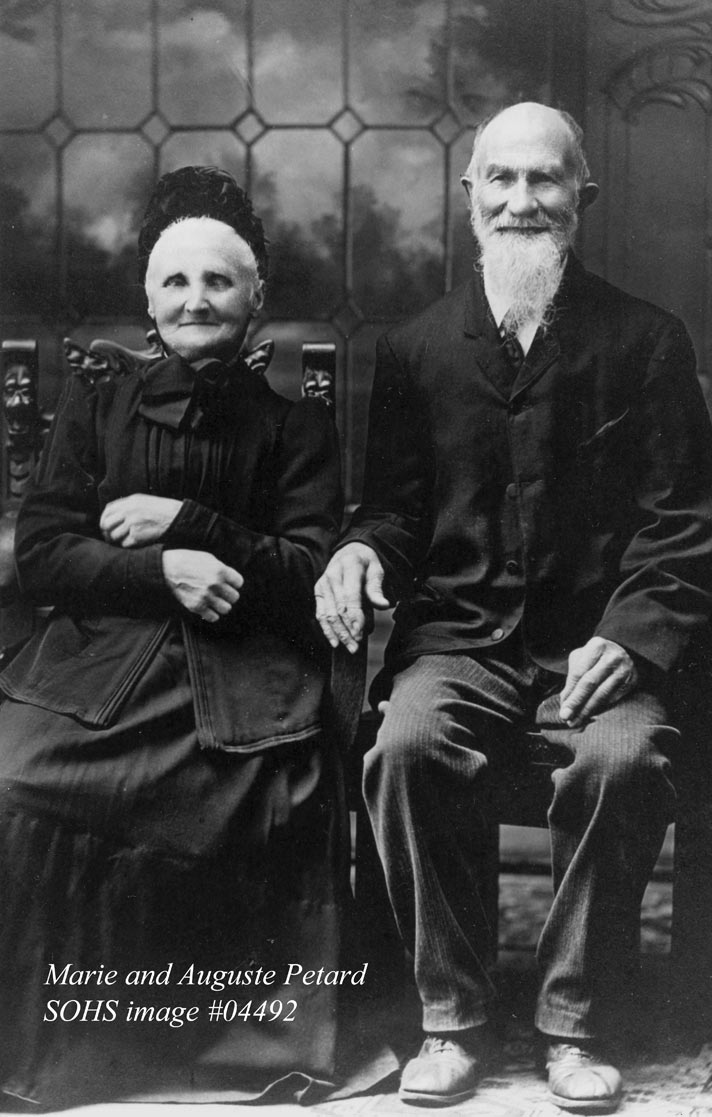

Auguste Petard was a “Johnny-come-lately” to the Jacksonville scene. Born in 1845 in France’s Loire Valley, Petard undoubtedly followed the winemaking tradition of the region. At age 30, he had married his wife Marie and by 1895 Auguste, his wife, and two sons were working in the Muscadet vineyards encircling Nantes.

However, stories of the gold still to be found in America made him dissatisfied with his life tending grapevines. In 1897, Auguste and his elder son left France for the riches of the new world. After brief stays in Nova Scotia and North Dakota, they headed for the California gold fields. But the Petards were 50 years too late. Setting out for the newer frontier of Alaska, they stopped over in Jacksonville.

One day became two, three, then a week. There was gold still to be had in Jacksonville—and there were vineyards and winemaking, something Auguste knew well. He purchased a little land at the foot of the hill next to the stream where Jacksonville gold was first discovered and sent for Marie and his younger son. By 1918, Auguste’s efforts had yielded enough gold for him to buy the adjacent hillside property. The Petards planted 20 acres of grapevines on the slopes and produced a little red and white vin ordinaire. A ditch Auguste constructed for hydraulic mining could also be used to irrigate the vineyards.

Life was good. A productive farm, healthy vineyards, enough money, and two devoted sons—what more could a couple want? There was this strange English word, “prohibition,” but what did it have to do with them? Besides, how could people possibly live without wine?

Then suddenly it was there—the 1919 Volstead Act. Virtue had triumphed over “demon rum.”

The Petards and other grape growers suddenly found no market for their grapes. Surely this was only a temporary setback! Auguste and his sons gathered the crop and made some wine for family use. The remaining grapes rotted in the storage shed.

Then rumors of the Petard’s “illegal wine” reached the ears of members of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. They’re selling “bootleg wine,” they announced and demanded the County Prohibition Enforcement Agent take action against these corrupt lawbreakers.

The agent notified the Sheriff. Armed with a search warrant, the two went to the Petard farm where they discovered at least 600 gallons plus 50 quarts of wine in aged and cobwebbed barrels and bottles. Moreover, there were 24 more empty barrels and 1,000 empty bottles “hidden” in the cellar! Auguste was charged with manufacturing and possessing intoxicating liquor.

The sheriff padlocked the storage shed but did not arrest the 80-year-old Petard. The W.C.T.U. was delighted that the contraband wine had been discovered but frustrated that the sheriff had not destroyed the barrels and poured out the contents. However, under the law, that was a decision for the courts.

The court deemed it prudent to remove the wine from any temptation, so the sheriff had the barrels loaded into trucks and deposited in the field below Jacksonville’s schoolhouse hill. Surely the town’s law-abiding citizens would not touch it!

The next day the court ruled that the wine had to be poured out. It was a ceremonious occasion—local ministers and 16 members of the W.C.T.U. gathered to watch the sheriff’s deputies bash the barrels with their axes and dump the wine.

Auguste pled guilty to the charges. He was fined $75, but a 30-day jail sentence was suspended, a decision loudly protested by the W.C.T.U. Auguste paid the fine and retired to his little farmhouse and abandoned vineyard.

His story is a sad illustration of the adage that “Timing isn’t everything; it’s only 99%.” You can contemplate this thought in the Oregon Wine Experience’s big tent at Bigham Knoll where, in 1922, $4,000 of Auguste’s wine soaked into the weeds….