Pioneer Profiles – March 2020

March is “Women’s History Month.” (Or perhaps, for these 31 days, we should call March “Women’s Her-Story Month.”) So for our March Pioneer Profile, we’re sharing the story of a special female pioneer.

Alice Eliza Hanley pursued drawing and painting until her father, Michael Hanley, developed dementia. As the eldest surviving unmarried daughter and deemed an “old maid,” it became her lot in 1885 to care for him until his death while she managed the household and helped with the family’s extensive land holdings. Michael required Alice’s complete attention and forbade her continuing her art. He became a demanding and “difficult patient” until two strokes in 1887 left him physically and verbally disabled. But the experience also gave Alice strength, fortitude, empathy, and vision.

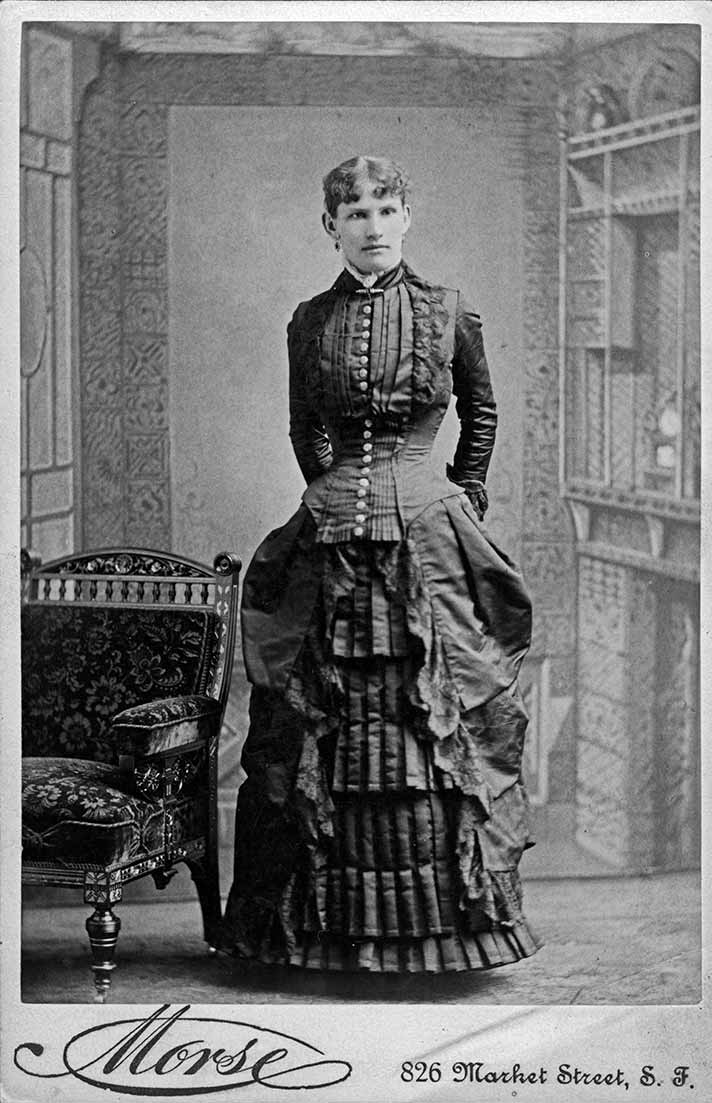

Born February 27, 1859, at “The Willows,” the family home on Hanley Road just outside of Jacksonville, Alice was the third of Michael and Martha Hanley’s children. Michael had purchased the 640-acre donation land claim in 1857. Martha had named it “The Willows” following her planting a beautiful willow tree in 1861 to honor the birth of Alice’s younger brother William.

As resources allowed, Michael added significantly to his original holdings accumulating thousands of acres near Jacksonville, on Butte Creek, and in Klamath Valley. He raised cattle, sheep, hogs, horses, and mules; grew alfalfa, oats, wheat, and corn which both fed his livestock and supplied Fort Klamath; was an original incorporator of the Ashland Woolen Mills which he supplied with wool from his sheep; and invested in a sawmill in Prospect. Hanley was deemed “the best stockman and agriculturalist in the country” operating one of the most diversified and lucrative agricultural and stock raising operations in Southern Oregon. According to tax records, he was the second richest “farmer” in Jackson County.

Following Martha’s death in 1887 from “pulmonary disease” and Michael’s death in 1889, the family properties were divided among the six surviving children. Alice inherited The Willows, the family homestead, along with 111 surrounding acres.

From her mother, Alice had developed a love of gardening; from her father, a passion for agriculture. She also recognized the unique time in which they lived. As a result, in addition to managing the home farm, Alice pursued three particular areas of interest—Extension work, garden clubs, and history.

In 1911, the Oregon Agricultural College (now Oregon State University) had established the Extension Service to serve communities beyond the college campus primarily in the areas of agriculture, home economics, and 4-H. Alice served on Jackson County’s first Extension committee and for some years served as chair. In 1914 the State Legislature agreed to match county funds appropriated for extension work. But saying and doing were two different things. Two year later to secure Jackson County’s matching appropriation, Alice and other Jackson County Extension members made hats and modeled them for the Legislature to demonstrate how Extension activities saved people money.

During World War I the focus was on “war work”—bandage making, baking with flour substitutes, and overcoming legislative obstacles for funding to carry out their work. Fairs also came under the auspices of the Extension, and in 1922 Alice was superintendent of the Women’s Building at the Jackson County Fair, using the opportunity to promote floral, culinary, art, textile, and furniture skills via booths, talks, and demonstrations.

Agriculture was a key part of the Extension’s charter, and Alice had extensive holdings to manage. She worked in the fields alongside her workers and made sure she kept up with the latest farm machinery. She studied horticulture and appeared before the Oregon Legislature on agricultural causes at her own expense, including advocating for the rights of female farm workers.

Alice was the first to notice Winter Blue Grass growing in the Valley. Thinking it was a pest, she consulted an Extension Service expert who determined it could be highly beneficial to the stock industry given that it was immune to cold, snow and pests; could sprout freely where other grasses wouldn’t grow; and was excellent winter pasturage for cows, sheep and hogs. As a result, she cultivated it and encouraged other farmers to do so as well.

In 1922, Alice also ran as an independent candidate for the State Legislature with a platform advocating agricultural issues and reducing taxes on farms. She was strongly opposed by the Ku Klux Klan whose members would show up at her rallies to heckle her speeches. She, along with many others on the ballot, lost to candidates endorsed by the Klan.

The gardens around the Hanley homestead were also a focus of Alice’s attention and she became a charter member of the Jacksonville Garden Club and very active in garden club work. She also stayed busy with her involvement with the grange, the Chautauqua in Ashland, and the Order of the Eastern Star (she was Worthy Matron three times).

From early on, Alice recognized that she had witnessed a unique historical era. Born shortly after the gold rush brought miners and settlers to the Valley, she had lived to see airplanes fly overhead; she had gone from riding her favorite white horse to driving her favorite white car. Her home became a repository of early Jacksonville history. As people moved away from Jacksonville, she would buy their possessions. At one point she noted, “My home may look like a museum, but all of the old furniture I have bought is practical and useful.”

She was also deemed one of the best sources on the settlement of Jackson County and a repository of local history. Her retentive memory made her able to document pioneer families, their traditions and history, sharing stories she had heard and events she has seen as a child.

Alice was President and founder of the Southern Oregon Pioneer Association. The association joined with the Sons of the American Revolution and the Daughters of the American Revolution in founding the Southern Oregon Historical Society. Their first goal was the preservation and restoration of the abandoned Jackson County Courthouse in Jacksonville which Alice did not live to see. But her adopted niece, Claire did.

Following the deaths of her oldest brother John and his wife Mary, their surviving children were farmed out to John’s brothers and sisters. In 1904, Alice took in their youngest daughter known as Claire. Claire remained at the Willows for the rest of her life, absorbing and expanding her Aunt Allie’s love for agriculture, horticulture, and history. Upon Alice’s death on July 3, 1940, Claire invited her two sisters—Martha and Mary—to live at the Willows with her.

The three of them continued to contribute to the farm. Claire sold 80 acres of land to Oregon State University so they could create the Southern Oregon Experiment Station, i.e., the Extension. Claire was a founder of the Southern Oregon Historical Society and assumed its presidency in 1950. Alice’s carefully preserved pioneer memorabilia became the core of the Jacksonville Museum’s collection. Mary became the Museum curator from 1955 to 1969, also devoting time to the farm gardens and her orchid collection. Claire died in 1963; Martha in 1975.

Mary continued to run The Willows until her death in 1986. She bequeathed the Hanley home, all outbuildings, the 1850s and 1910 historic barns, the 1850s springhouse, and 37 acres to the Southern Oregon Historical Society so that future generations could learn about early day farming in the Rogue Valley. When Mary passed in 1986, women had been operating the Hanley Farm for over 100 years.