Pioneer Profiles – April 2020

In the mid-1800s, California and the Oregon Territory seemed like the “promised land” to individuals in the eastern United States dreaming of riches, adventure, or better lives. But first they had to get here. There were basically two routes—by land and by sea. This month and next, we’ll describe the experiences of pioneers who chose each alternative.

From 1843 to the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, some 500,000 emigrants traveled the Oregon and California Trails in search of new homes and the riches the West had to offer. First to come were the settlers. In 1841, a lonely caravan of 58 people followed the trails laid by fur trappers and traders, half coming to Oregon and half following a land route to California. Beginning with “The Great Migration of 1843” when an estimated 700 to 1,000 emigrants left for Oregon, this trickle became a flood. After the Mexican War ended in 1847, another 4,000 ventured west.

The 1848 discovery of gold in California dramatically changed the character and experience of traveling the trails. Men dropped everything in a rush to get to California. By the end of 1849 over 25,000 more people had traveled the California Trail. The following year another 55,000 migrated to California; 50,000 more came in 1852.

Congress’s Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 added to the emigration. It offered free land in the Oregon Territory—320 acres to married settlers, 160 to unmarried settlers—providing that they occupied it for four consecutive years.

Independence, Missouri, was the main starting point for the 2,000-mile journey across the Oregon Trail to Oregon City. After selling their land, machinery, livestock, and household goods, most emigrants journeyed by steamboat from St. Louis to Independence Landing where, with their ready cash, they purchased the supplies they would need for the long trek and a fresh start in the new territory. It was a difficult journey and took four to five months by wagon. Ideally, wagons departed in April so they could traverse the Rockies and Cascades before the early snows set in.

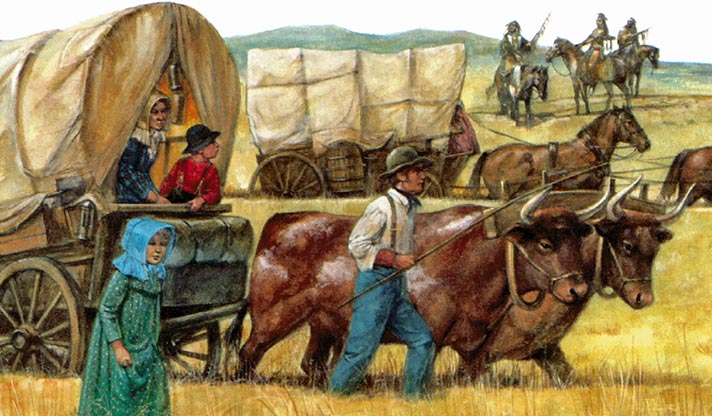

No one wanted to cross the unknown prairie alone, so people traveled in groups, or “trains,” for safety and mutual assistance during the long trek westward. Groups usually consisted of relatives or neighbors from the same hometown. Some groups were members of the same church. A few small towns packed up completely and moved west together.

A typical wagon train might have 30 wagons, although some had upwards of 200. Traveling as a group, emigrants could afford to hire a guide, usually an old mountain man who could find the Trail and select good places to camp.

The country that lay ahead contained no towns or settlements, so a successful journey required organization. The most successful groups had a written code, “constitution,” or ad hoc agreement. Sometimes they formalized these arrangements, forming joint stock companies.

Almost all wagon trains had regulations of some sort along with elected or appointed officers. Once they left town, they also left any formal law enforcement. The officers of the train became responsible for maintaining order and punishing rule-breakers. Rules typically covered everything from camping and marching to restrictions on gambling and drinking with penalties for infractions.

When it finally became time to depart, it became a mad rush with groups trying to leave at the same time to gain first access to Trail resources. Massive traffic jams of wagons were made worse by the inexperience of green East Coast teams.

The first miles were a hubbub. Ill-broken oxen and reluctant mules bolted or sulked in harness, tangled themselves in picket ropes or escaped entirely and sped back to the starting point. When not busy rounding up livestock, the men, exuberant to finally be underway, quarreled over firewood and water holes and raced for preferred positions in line.

Once under way, 15 miles was considered a good day’s travel. After several days on the Trail, most wagon trains settled into routines. A typical day started before dawn with breakfast of coffee, bacon, and “Johnny cakes” made of flour and water. Bedding was secured and wagons repacked in time to get underway by seven o’clock. At noon, a train would stop for a cold meal of leftovers prepared that morning. Then back on the Trail again.

Around five in the afternoon, when a good campsite with ample water and grass was found, a train would stop to set up camp and circle the wagons for the evening, creating a corral to secure the livestock. Men made repairs while women cooked a hot meal. Evening activities included schooling the children, singing and dancing, and telling stories around the campfire. By eight, the camp would settle down for the night and the men go on guard duty. Except in terrible weather, most travelers cooked, ate and slept outside.

Meals were pretty much the same every day—bread, beans, bacon, ham, and dried fruit over and over again. Occasionally there might be fresh fish or game. Many families took along a milk cow so they could have fresh milk. However, coffee was the staple beverage. It was drunk by adult, child, and beast as the best way to disguise the taste of bitter, alkali water.

Some wagon trains stopped every Sunday; others reserved only Sunday mornings for religious activities and pushed on during the afternoon. Even a half-day break gave the oxen and livestock a needed rest and gave the women a chance to do laundry.

Pioneers who had tried to “take it all” found themselves discarding articles along the way. Difficult stretches of the Trail were littered with piles of “leeverites”—items the emigrants had to “leave ‘er right here” to lighten their wagons and spare weary oxen.

The tiring pace of the journey, almost always on foot, caused more than one emigrant to go insane. And perils along the way caused many would-be emigrants to turn back. For weeks the wagon trains crossed vast grasslands which were hot by day and cold at night. Often violent thunderstorms with hail, lightening, tornadoes, and high winds swept down on the hapless travelers. The dust on the Trail itself could be two or three inches deep and as fine as flour.

River crossings were often dangerous. Even if the current was slow and the water shallow, wagon wheels could be damaged by unseen rocks or become mired in the muddy bottom. If dust or mud didn’t slow the wagons, stampedes of domestic herd animals or wild buffalo often would.

Indians were among the least of the emigrants’ problems. The Indians were more interested in trading or in stealing livestock. Tales of hostile encounters far overshadowed actual incidents, and relations between emigrants and Indians were further complicated by trigger-happy emigrants who shot at Indians for target practice. Historical studies indicate that between 1840 and 1860, Indians killed 362 emigrants, but emigrants killed 426 Indians.

Nearly one in ten who set off on the Oregon Trail did not survive. The two biggest causes of death were disease and accidents. Gastrointestinal illness and typhoid fever were common. Cholera meant almost certain death. Accidents were an ever-present possibility, frequently exacerbated by negligence and exhaustion. Being crushed by wagon wheels, drownings, and livestock stampedes were the biggest accidental killers on the Trail. Shootings were common, but murders were rare.

The Oregon Trail is this nation’s longest graveyard. The number of deaths which occurred in wagon train companies is conservatively figured as 20,000 for the entire 2,000 miles of the Trail, or an average of ten graves per mile.

Oregon’s image was that of a place of renewal, where everything was bigger and better and people could better themselves. But as the emigrants pushed overland, many lost sight of the vision that had set them going. As one pioneer recalled, “The Trail was strewn with abandoned property, the skeletons of horses and oxen, and with freshly made mounds and headboards that told a pitiful tale.”

Yet most travelers summoned up reserves of courage and kept going. And not long after Oregon achieved statehood in 1859, veterans of the Oregon Trail realized the historic importance of their journey. Founded in 1877, the Pioneer Society of Southern Oregon held annual meetings, published memoirs of trail experiences, and sought to document and preserve details of this great adventure. This mission continues today under the auspices of the Southern Oregon Historical Society, Historic Jacksonville, and other local heritage organizations.

Next month: “Two If by Sea.”