The Count of Monte Cristo was penned as an adventure novel by Frenchman Alexandre Dumas in 1844, set in the midst of the political conflicts between Napoleon and the French monarchy of that time. “The book is considered a literary classic today. . . . ‘The Count of Monte Cristo has become a fixture of Western civilization’s literature, as inescapable and immediately identifiable as Mickey Mouse, Noah’s flood, and the story of Little Red Riding Hood.”

The novel was adapted into a five hour English language play by the French-Anglo actor, Charles Fechter, first performed in London in 1868. Even at 5 hours, the Fechter play omitted whole sections and numerous characters of the book, and tweaked the story, with alterations of the plot and characters’ relationships to make it a more effective stage drama. Fechter continued to perform the play through 1878, further abridging the story and shortening the play over time. The Fechter play was revived, revised, and abridged to a more manageable scope and duration by James O’Neill (father of playwright Eugene O’Neill, who wrote of the play’s impact on his family in Long Day’s Journey Into Night) in 1883 and remained a staple of the elder O’Neill’s stage career for the rest of his life. The O’Neill revision of the Fechter adaptation of the Dumas novel is the starting point for the production of the play being presented this season by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival (OSF) on the expansive stage of the open air Allen Elizabethan Theatre.

If you’re erudite enough to be so interested in the play that you’re reading this review, then your education at some time probably included a reading of the book, which has become a staple in the course of any decent education in America today. If you are one of the few who haven’t read it, (but you ARE interested enough to be reading THIS), then it is incumbent upon you to get to a library or bookstore to access a copy of the novel and read it already, so you don’t remain ignorant among most of your peers. Since everyone has read the novel, or should, don’t expect this review to present a summary of the plot which you should already be familiar with. (Get your spoilers from recalling, or reading, the novel, and spontaneously discover and react to the plot and relationship changes injected by adapters Fechter, O’Neill, and OSF when you see the OSF production.)

What I DO want to write about is the interesting OSF production – what worked and what didn’t. Is it good? YES, absolutely. Is it perfect? No, it has its flaws. Should you see it? YES. Certainly, if you haven’t yet ever seen a stage production of The Count of Monte Cristo (as noted above, the story “has become a fixture of Western civilization’s literature” and the archetypal illustration of the idea of revenge), your cultural life will be more complete for seeing this one. Even if you have previously seen The Count of Monte Cristo performed on stage, this production has its virtues which make it well worthwhile to see this one.

Fechter adapted the novel for the stage in the era and style of 18th Century French melodrama. Melodrama is a style of stage work that differs in a number of respects from the more realistic style of drama which we are generally accustomed to seeing when we see a stage play in a contemporary theater today. In melodrama, the plot takes precedence over detailed characterizations (characters are simply drawn and stereotyped), and various plot elements tend to be exaggerated: “pathos, overwrought or heightened emotion, moral polarization (good vs. evil), non-classical narrative structure (e.g., use of extreme coincidence and “deus ex machina”), and sensationalism (emphasis on action, violence, and thrills)” [Wikipedia, Melodrama, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melodrama]. Melodrama often employs music or sound effects to emphasize and heighten emotion and announce coming plot developments. O’Neill’s revision of Fechter’s play retained the melodramatic style of the work, and OSF too has retained and exploited the melodramatic nature of the work.

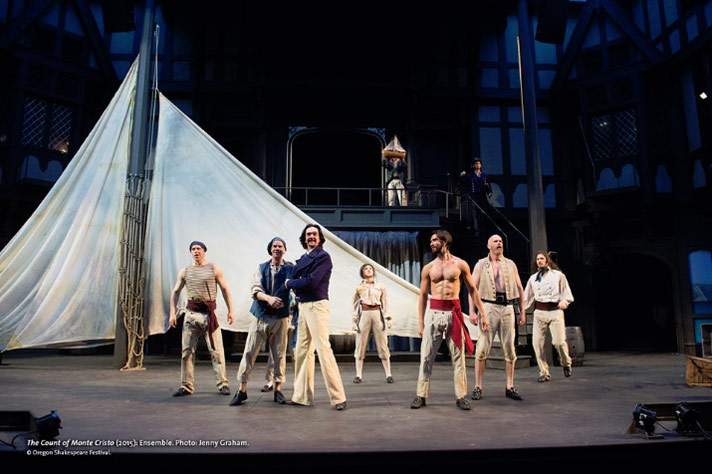

OSF excels in the theater technical arts essential to present an effective melodrama: sound, music, staging, choreography, props, set design. And those all came together in this production of The Count of Monte Cristo. Immediately, on walking into the theater, before the performance has even begun, the audience is confronted with an imposing set, featuring several larger than life sails on a giant mast, with the theater sound system softly playing background sounds of realistic ocean waves lapping and seagulls vocalizing – one is immediately transported to the world of the seagoing ship Pharaon at dock in Marseille and its first-mate and acting captain, Edmond Dantes. Sound is employed repeatedly and effectively in this production to provide emphasis and momentum. A variety of cast members take turns during the performance, sitting stage right and operating a slapstick – a percussion instrument that produces a sound like the crack of a whip at appropriate moments to provide emphasis. An orchestral bass drum, appropriately dressed for the occasion, is also brought out and used, to provide driving momentum to several scenes.

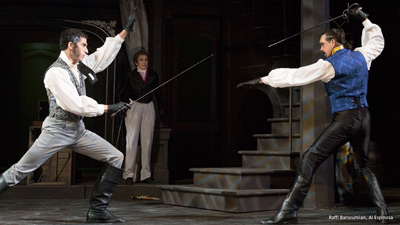

This show is not a musical, yet music is used throughout to set moods and express emotions. There is a little on-stage guitar strumming at one point. There’s some fine singing in this production by two of the singers (Bonnie Milligan and Michelle Mais ), who also are the most memorable singers of The GoGo’s tunes in the musical, Head Over Heels, which is in repertory on the same OSF stage with The Count of Monte Cristo. At one appropriate point, Ms. Milligan, costumed for the part, sings an operatic aria from a second story perch, which the audience thoroughly appreciated and set just the right tone for the scene in which it was injected. OSF assimilates a little of everything from everywhere, to produce just the right melodramatic touch – a sea of waving pendants by a troupe of “Namigo” (“wave persons”) borrows a technique used in Japanese theater to depict a roiling sea. The choreography, an OSF high point, is effectively employed in several ways – to illustrate the joy of returning sailors to their home port, through dance (see lead photo above), and most especially in a thrilling, extended sword fight which is a highlight of the second act.

Edmond Dantes (Al Espinosa) seeks revenge against one of his wrongdoers, Danglars (Raffi Barsoumian) in an extended and well choreographed swordfight in Act 2 of OSF’s The Count of Monte Cristo.

So, with all of that working, you have to be wondering why I commented above that this production isn’t perfect and has flaws. Let me begin to explain by relating that at intermission, the woman sitting on my left turned to me, grimaced and commented, “Gee, that was BORING!” The gentleman seated to my right agreed with her. If there is ONE word that ought never be applicable to a melodrama, that’s the word: boring. Melodramas are supposed to be “over-the-top”, overwrought, polarized, emotionally intensified – quite the opposite of boring. Part of the problem was the story plotted in the Dumas book – to a degree the play is stuck with some plodding plot development which is not overly conducive to melodramatic treatment. If you’ve ever tackled the challenge of getting through the book, great as it is, it’s just plain plodding at points, more so in the early going than further along. I quibbled with my audience neighbors – yes, the show (through the first act) was flawed, but it really was NOT boring. The scene near the end of the act where a body is thrown off of an upper story balcony (dock) into a roiling sea (the waving pennants) and then Edmund Dantes suddenly springs up in the middle of the sea is certainly not boring, but rather very effective melodrama.

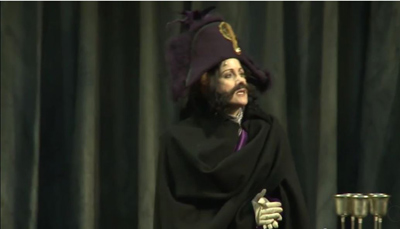

What was missing was power – the acting, which should be eye-rolling, near histrionic and nearly overdone in gesture, movement and PASSION, in a melodrama was in too many places flat. To be sure, this was not universally the case. One actress in particular delivered an unforgettable, energetic, dramatic and comedic turn that nearly stole the show (and certainly kept the first act from being boring): Robin Goodrin Nordill as Noirteier, sister of the Royal prosecutor Villefort, and also a Bonapartiste sympathizer surrounded by loyal Royalists. The Noirtier role (modified from the father of Villefort in the Dumas book, to his brother in the Fechter adaptation, and very cleverly and effectively changed to his sister by OSF here) calls on the actress to don a successive series of different disguises, most in gender-bending cross-dressing costumes and personas. Ms. Nordill tackled the role with relish, energy, passion, obvious enthusiasm, and terrific comedic touch – one couldn’t have asked for more or better in that part – NOT BORING!

Noirtier (Robin Goodrin Nordill), sister of the Royal prosecutor, in male disguise in Act 1 of OSF’s The Count of Monte Cristo.

Another actor also delivered an inspired performance worthy of a melodrama, in the first act: Derrick Lee Weeden as Faria, the fellow prisoner with Edmond Dantes in the Château d’If prison, who mentors and sustains Dantes there. Faria bequeaths his fortune to Dantes, and in his final gesture, engineers Dantes’ escape, by instructing Dantes to take the place of his corpse in its body bag on his death, and thus be thrown into the ocean, with a means to escape the bag too. Mr. Weeden’s performance was spot on – not too over-the-top, but definitely not flat.

Edmond Dantes (Al Espinosa) embraces fellow prisoner Faria (Derrick Lee Weeden) upon receiving Faria’s treasure map in Act 1 of OSF’s The Count of Monte Cristo.

The cast must have guzzled copious amounts of coffee during intermission, because from the moment they hit the stage for the second act, through the finale, it was a different atmosphere- fully engaged, energetic, very melodramatic acting on everyone’s part. When the stage lights went out and the house lights came up, my two audience neighbors both turned to me with smiles on their faces; the woman on my left commented “THAT was much better!” and the gentleman on my right nodded in agreement. The second act was filled with artful and notable performances, as well as a bevy of sensational scenes, such as the signature swordfight mentioned above. In Act 2, Al Espinosa burst with energy as Edmond Dantes, in every scene, whether confronting broken relationships with his left-to-fend-for-herself-while-pregnant betrothed, Mercedes Mondego (Vilma Silver) and born-after-he-was-imprisoned son, Albert Mondego (Dylan Paul), swordfighting with antagonist Danglars (Raffi Barsoumian), word-playing with innkeeper Caderousse (Richard Elmore) or with successor to Mercedes’ affection, Fernand Mondego (Michael Sharon), challenging another antagonist Villefort (Peter Frechette) in a duel, or emotionally shouting the score as the plot moves towards it’s conclusion: “THAT’S ONE!”, etc. All of the other actors, just mentioned, turn in fine, melodramatic performances in Act 2. Maybe Act 1’s languor was just an off night during a long string of night after night repertory performances. No matter, whatever the cause, it was fixed before the conclusion of intermission, and even my critical audience neighbors would admit this Count of Monte Cristo is a production well worth attending. The woman who earlier commented that “That was boring”, left the theater remarking, “I’m going to see that AGAIN!” Hurry up and get your tickets to see it a first time, before repeat visitors sell it out!

The Count of Monte Cristo will be running in repertory in the theater through October 11, 2015. OSF is also currently running eight additional plays in repertory with The Count of Monte Cristo: Head Over Heels and Antony and Cleopatra also in the Allen Elizabethan Theatre; Guys and Dolls, Much Ado About Nothing, and Secret Love In Peach Blossom Land in the Angus Bowmer Theatre and Pericles , The Happiest Song Plays Last and Long Day’s Journey Into Night in the Thomas Theatre. For tickets, call the OSF box office at 800-219-8161 or order online at http://bit.ly/1yqvboU.

Featured image caption: Edmond Dantes (Al Espinosa) and crew of the ship Pharaon (Ensemble) display elation (through dance) upon returning to home port of Marseille during opening of OSF’s The Count of Monte Cristo. Photo by Jenny Graham.

Lee Greene was born & raised in a NJ family where the only religion worshipped was classical music, Leonard Bernstein was God, and the radio was constantly on and tuned to classical station WQXR (which is now always on in his Jacksonville home thanks to the miracle of the Internet). Growing up in the New York City metropolitan area and later while residing and practicing law in NYC, Lee attended oodles of Broadway and off-Broadway theater productions, as well as concerts and opera at Lincoln Center, Carnegie Hall and other NYC venues. Lee is now a retired attorney, runs a computer support business, and has served on the boards of Rogue Opera & Siskiyou Violins. Lee also writes Performing Arts reviews published on the website,

Lee Greene was born & raised in a NJ family where the only religion worshipped was classical music, Leonard Bernstein was God, and the radio was constantly on and tuned to classical station WQXR (which is now always on in his Jacksonville home thanks to the miracle of the Internet). Growing up in the New York City metropolitan area and later while residing and practicing law in NYC, Lee attended oodles of Broadway and off-Broadway theater productions, as well as concerts and opera at Lincoln Center, Carnegie Hall and other NYC venues. Lee is now a retired attorney, runs a computer support business, and has served on the boards of Rogue Opera & Siskiyou Violins. Lee also writes Performing Arts reviews published on the website,