Pioneer Profiles – July 2019

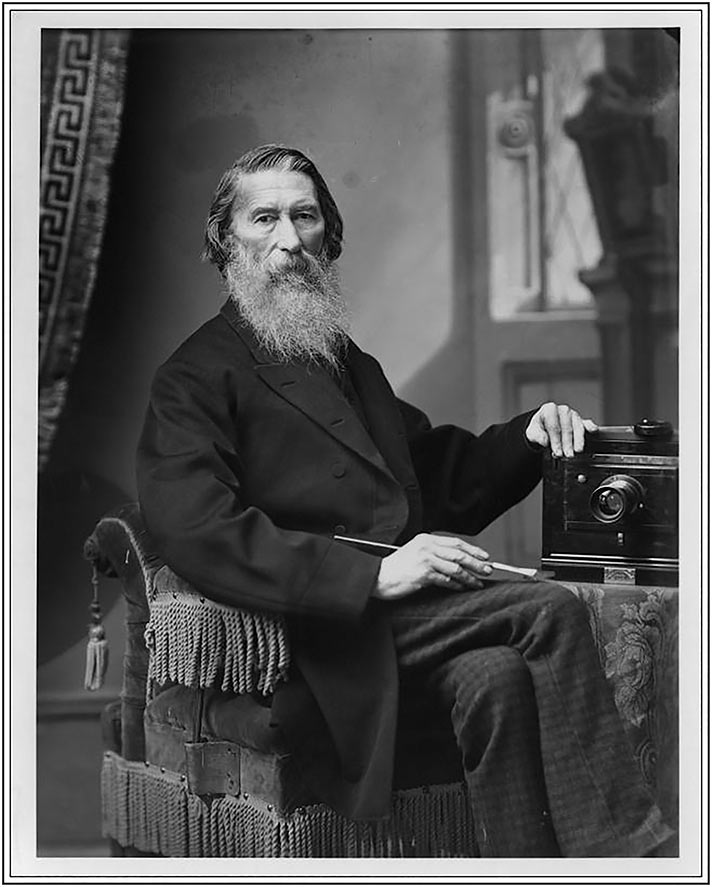

It’s Britt season, so what better subject for summer’s Pioneer Profiles than Peter Britt, whose pioneer homestead is now the site of Britt Festivals, the Britt Gardens, and portions of Jacksonville’s Woodlands Trail System. Perhaps best known as the pioneer photographer who documented Southern Oregon’s people, activities, and landscapes from the 1850s to 1900, Peter Britt was also a visionary, a painter, a respected horticulturalist, a vintner, and an entrepreneur.

Family tradition claimed that Britt was of English ancestry and that his forebears had migrated to the Swiss Alps. He was born in 1819 in Obstalden, in the Swiss canton of Glarus, where his family had farmed land for centuries.

However, Britt’s talents led him to pursue painting. Although his interest lay in nature studies and landscapes, his income came from portraits, and he wandered Switzerland, Germany, and possibly France as an itinerant portrait painter. According to Alan Clark Miller’s 1972 thesis, “Peter Britt: Pioneer Portrait Photographer of the Siskiyous,” paints and canvas were scarce so Britt improvised by grinding minerals and mixing them with oil and other pigments to create paints and weaving flax grown on the family farm into canvases.

In 1845, Britt immigrated to the United States with his father Jacob, his brother Kaspar, and Kaspar’s family, settling in a community of Swiss émigrés in Highland, Illinois. Although continuing to work as a portrait painter, Britt faced increasing competition from the new art of “daguerreotyping.” According to Miller, Britt set about to master this new technology, even traveling to St. Louis to study with John Fitzgibbon, who, by contemporary newspaper accounts, was universally known in the U.S. and in Europe as one of the oldest and most successful operators of the daguerrean and photographic arts. In 1847, Britt apparently opened his own daguerreotype studio and operated it for the next five years.

Then, listening to the stories of returning “Forty-niners,” Britt joined the ranks of émigrés stricken with gold fever. In the spring of 1852, shortly after he became a naturalized citizen, Britt and three companions headed west on the Oregon Trail, the beginning of a five-month journey. At Grande Ronde Valley, two of the men refused to continue dealing with Britt’s 300 pounds of photographic equipment. There they separated, and Britt and his wagon master continued on to the village that was to become the city of Portland. Hearing news of the gold strike in Table Rock City (now Jacksonville), Britt decided to venture south and walked from Portland to Jacksonville, arriving November 8, 1852, with a two-wheeled cart of photographic equipment, a yoke of oxen, a mule, and five dollars in his pocket. He camped on the site now known as “Britt Hill,” possibly filing a donation land claim, and built a small log cabin on a hillside site that boasted a magnificent view.

A 1920 article in the Jacksonville Post recalls¸ “At that time mining excitement was at its height. The hills and gulches for miles around were staked, and men were making good wages with rocker and ‘long tom.’ Mr. Britt, with several others equally inexperienced in mining, took a claim on Ashland Creek. They built sluice boxes and for two weeks worked hard. In the evenings they discussed what they would do with their money when they made a cleanup. They finally decided upon going to South America, where they heard there were good opportunities to be found. When the cleanup was made it netted them 75 cents each, and the South American trip was indefinitely postponed.”

That cured Britt of any mining fever. He soon recognized that “mule skinning” was a much more profitable bet and purchased a string of pack mules. For several years, he and fellow Swiss compatriots Kaspar Kubli and Viet Shutz made the arduous ten-day trek between Crescent City, California, and Jacksonville, hauling foodstuff and mining tools.

With the grubstake he accumulated, Britt bought a state-of-the-art camera in San Francisco and returned to the photographic trade, opening “P. Britt’s Photograph and Daguerreotype Room” in 1856, where people came from all parts of Southern Oregon to have their photographs taken. The Britt photography studio now became a full-fledged enterprise, and Britt became the best-known and most popular photographer in the southwestern Oregon and northern California area. Best known for his portraits, Britt photographed almost all of the prominent citizens as well as farmers, miners, Chinese workers and Native Americans.

In the 1860s, Britt purchased a stereo camera which allowed him to also pursue landscape photography. In 1874, Britt, accompanied by his son Emil, was the first person to photograph Crater Lake. The trip was arduous, the weather uncertain, and his previous attempts in 1868 and 1869 had failed. There were no roads to the lake, and photographic equipment, camping gear, and provisions—amounting to several hundred pounds—all had to be packed in. The resulting photographs were used to substantiate the need for making Crater Lake a national park. However, Britt’s diary for that day only noted that “Emil has the sniffles.”

Britt should not be considered merely a photographer, however. He engaged in numerous other business activities, nearly all of which were profitable. These other aspects of Peter Britt will be explored in the next two issues of the Review.

Pioneer Profiles is a project of Historic Jacksonville, Inc. We’re offering a full summer of fun and interesting tours that provide a new look at local history and bring it to life! Visit us at historicjacksonville.org and follow us on Facebook (historicjville) and Instagram for a full schedule of activities and events plus local history trivia and fascinating random historical facts. See event ads this page.