Pioneer Profiles – December 2016/January 2017

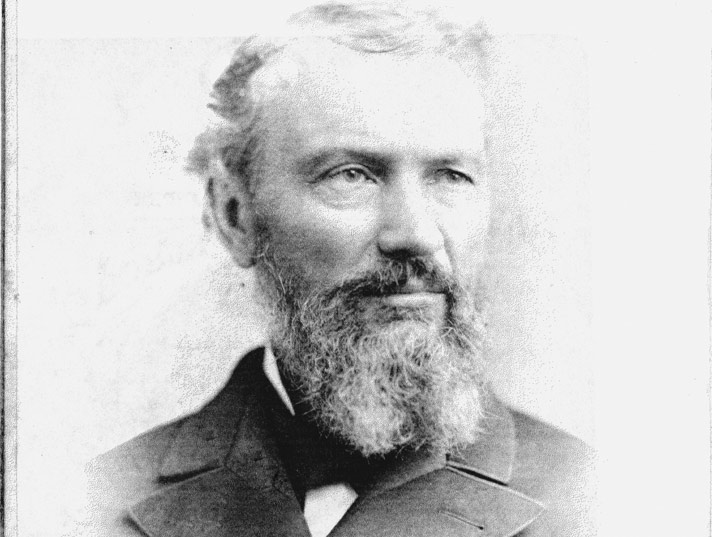

With a Supreme Court position and numerous judgeships around the country sitting vacant waiting for U.S. Senate approval of Presidential appointees, this month’s profile focuses on local lawyer, District Judge, and Oregon Supreme Court Justice Paine Page Prim.

Prim’s beginnings were inauspicious. He was born in Wilson County, Tennessee, on May 2, 1822, the son of a poor farmer who died when Prim was a boy. As a “man of the family,” he had his mother and three siblings to look out for.

Schooling was intermittent until there were sufficient resources for Prim to spend a year and a half at an academy. He then taught school for a few years until he had the means to study law. In 1848, he was the first graduate from the Cumberland University School of Law at Lebanon, the first law school in Tennessee and the first west of the Appalachian Mountains.

After passing the bar, Prim practiced law in Sparta, Tennessee, but like many other ambitious young men, he soon saw the west as offering greater opportunities. In the spring of 1851 he joined a wagon train leaving Independence, Missouri, headed for the Oregon Territory.

Upon arriving in the Willamette Valley, Prim found there was little demand for his legal services. He filed a Donation Land Claim near Albany but soon tired of the monotony of farming. When news of the rich gold strikes in Jackson County reached him, Prim abandoned his land claim and headed to Jacksonville. Prim mined for the next four years, but also found his legal counsel occasionally in demand.

In 1853, Prim advised a popular miner named Springer whose claim had been jumped after Springer fell on hard times. The Alcalde (a position combining mayor and judge) ruled in favor of the jumper, a decision that did not sit well with many of the other miners who thought the Alcalde had been bribed or that the sentence was too harsh.

According to Uncivil Disobedience by Jennet Kirkpatrick, Prim then led a group of vigilantes who fashioned their own tribunal, “cheekily calling themselves the Jacksonville Supreme Court. The vigilante court convened, finding both the claim jumper and the justice of the peace guilty. In an unusual turn of events, neither was killed or harmed.”

Prim justified vigilantes superseding the authority of the Alcalde by citing “the omnipresent power of the people” as the source of law: “Who made this scoundrel judge? The people; and if the people possess the power to appoint one man to hang another, may they not make court high enough to hang, if need be, another court that they have made?”

By 1856 there was sufficient demand for Prim’s professional services for him to resume a law practice. He set up shop at 155 North 3rd Street in Jacksonville, an address which continued to house lawyers for the next 100 years. That same year the Oregon Territorial Governor appointed Prim the first District Attorney of the First Judicial District consisting of Jackson, Josephine, and Douglas counties.

Prim’s prestige grew. In 1857, he was elected one of four Jackson County delegates to Oregon’s Constitutional Convention. During the convention’s year-long debates, Prim supported an amendment to exclude Chinese from entering the new state, describing them as “evil.” Prim also opposed allowing blacks to settle in Oregon. Although Oregon was established as a “free state” instead of a “slave state,” that does not mean that early residents made ethnic or cultural minorities welcome.

In 1857, Prim also married 18-year-old Theresa Stearns who was half Prim’s age. A native of Vermont, she had crossed the plains with her parents four years earlier and settled with them on a farm near Ashland. Within a year, the Prims’ first child, Ella, was born and son Charles followed one year later.

Charles’s birth coincided with Oregon statehood. Perhaps in recognition of his work on the State Constitution, Prim was appointed Associate Justice of the Oregon Supreme Court and ex-officio Circuit Judge of the First Judicial District. Prim was a Circuit Judge and Supreme Court Justice for the next 21 years, including three terms as Chief Justice.

Prim’s judicial duties required him to be gone from home for extended periods of time, leaving his young wife alone with two infants. This did not sit well with Theresa, who decided she no longer loved him. She began treating Prim with contempt. According to one source she even told Prim that his company had become offensive, that she would prefer he stay away permanently, and that she was only happy in the “society of others.”

Although there was no evidence of hanky panky, Theresa’s reference to the “society of others” made Prim think she was having an affair. He kicked her out of their home. Theresa took the children and returned to her parents. She didn’t exactly pine away since local papers reported her taking pleasure trips to San Francisco.

Prim waited three years before filing for divorce. He charged Theresa with broadcasting her indifference to all, subjecting him to public ridicule, and refusing to cohabitate. He described her treatment of him as being “so harsh, cruel and inhuman…that his life had been rendered ‘burdensome.’”

Even with all this public airing of dirty laundry, Prim never finalized the divorce. After three postponements of the proceedings, he had the divorce stricken from the docket and began re-courting Theresa. By 1867 he had won her back and a year later their youngest daughter, Ida May, was born. Prim had local contractor David Linn design and build the family “a flamboyant house” where the Jacksonville “Buggy Wash” now stands.

When Prim was not elected for an additional judicial term in 1880, he resumed his Jacksonville law practice. He returned to politics two years later when he was elected to the state Senate where he served for two terms before again retiring from politics.

Prim continued to practice law for the next 10 years, including a stint as Attorney for the Southern Pacific Railroad. Theresa opened a millinery store which was well supported by local ladies seeking “the latest novelties in millinery, trimmed hats of every style, ribbons, and good kid gloves.”

In 1897, with Prim’s health failing, the couple “removed to San Francisco.” A year later, The Tidings reported that “Mrs. P.P. Prim is keeping a boarding house at 817 Eddy Street.”

Prim died in San Francisco on August 7, 1899. He is buried in the City section of the Jacksonville cemetery; a small slab headstone reading P.P.P. marks his grave. Theresa spent the last 14 years of her life in Chicago with her youngest daughter. She too is buried in the Jacksonville cemetery next to Prim, but her grave has no marker. Perhaps her incognito grave reflects one of Paine Page Prim’s reputed quotes: “Women should not have property rights as soon as they are married, even when they had property rights before marriage.”