Pioneer Profiles – February 2019

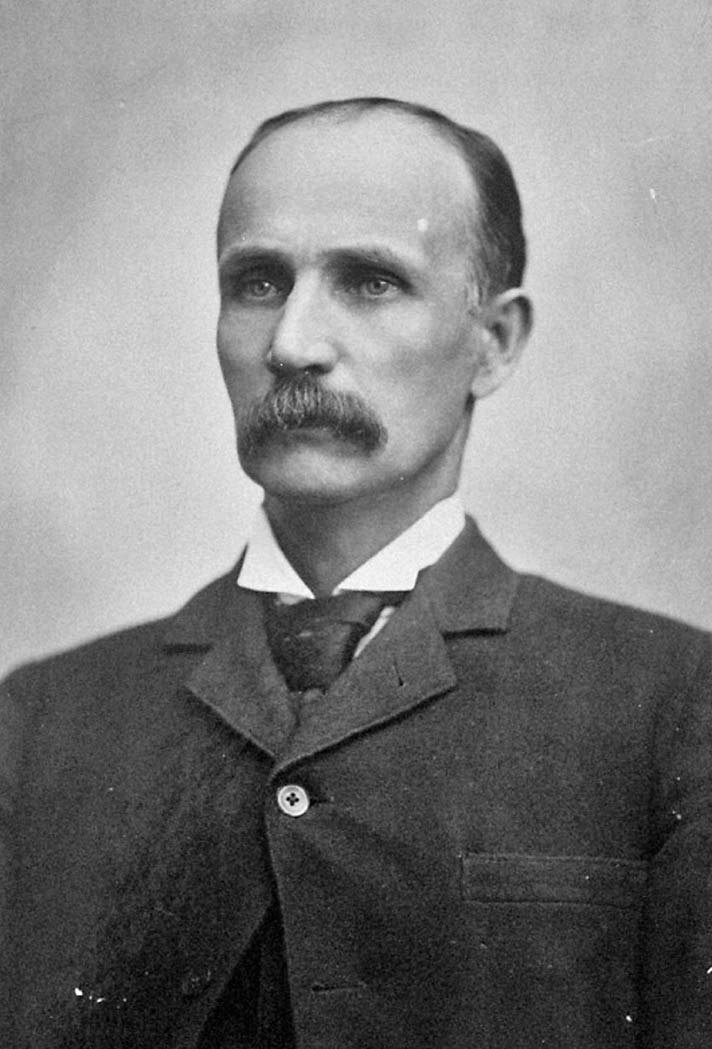

Given the two-month time lapse since Part 1 of William Mason Colvig’s pioneer profile, let’s begin with a quick recap of the Judge Colvig story.

Born in Missouri in 1845, Colvig had crossed the plains to Oregon at age six. An ox-drawn covered wagon was his alma mater with his mother teaching him to read during the five and a half months they sped “dizzily over the plains at the rate of 10 or 12 miles a day.” His father staked a land claim on the Umpqua near Canyonville and Colvig grew up with Indian children as playmates. He learned Chinook, the trading language between whites and Indians and later declared that he could “do it better than English.”

Largely self-educated, Colvig was an avid student and became an authority on Shakespeare. Enlisting in the Union Army when he turned 17, he was by turns a soldier, Indian fighter, mapper of Crater Lake, oil mine driller, pump operator, company store manager, hemp plantation foreman, law student, teacher, historian, publisher, rancher, lawyer, school superintendent, and District Attorney of Jackson County when it also encompassed Josephine, Klamath, and Lake counties.

In his 20s, he had aspired to become a Shakespearean actor. He did become a noted public speaker but even in his late 60s Colvig lamented that the world had been robbed of “a great actor and imposed on the innocent public an indifferent lawyer.”

Colvig appears to have begun practicing law when he returned to Oregon and married Addie (Adeline) Birdseye in 1879. However, he did not take the bar exam until after his election as District Attorney. He later supported a bill requiring a lawyer to have passed the bar before being elected to a public office.

Colvig’s title of “Judge” was an honorific. One story has him acquiring the title while serving as an arbiter of a turkey raffle. He remembered it being because he was judge at a baby show. Someone else recalled him saying that the only thing he was judge of was good whiskey.

The family had moved to Jacksonville in 1882 after Colvig’s election to public office as County School Superintendent. They remained here for the next 24 years, raising their children.

After retiring to private practice following his third term as District Attorney, Colvig remained in the spotlight. He was attorney for the Southern Pacific Railroad in Jackson County for several years, and even had the honor of having a station just south of Grants Pass named “Colvig.” He ran for State Senate and was a candidate for Presidential Elector. Given his educational experience as teacher, County School Superintendent and Board member, he was appointed to the Oregon Textbook Commission and served for 12 years. He was the Supreme Overseer of the Ancient Oregon of the United Workmen (A.O.U.W.), a fraternal organization providing mutual social and financial support after the Civil War.

Colvig was “known to be one of the best and wittiest public speakers in Oregon,” entertaining and engaging audiences on such topics as politics, pioneer history, and the Indian Wars and interweaving personal experiences into his narrative. In 1902, Salem, noting his “state reputation as an orator,” invited him to be the principal speaker at “the biggest celebration on the Fourth of July of any town in the Willamette Valley.”

Colvig later noted that “it rained with Willamette Valley vigor,” and he delivered his address to three thousand umbrellas. “The rain almost drowned the parade, and the Goddess of Liberty at its close, looked like a mermaid just fished from the bottom of the deep blue sea.”

With Medford becoming the commercial center of the Rogue Valley after the railroad bypassed Jacksonville, Colvig purchased both residential and business space in Medford and joined the Medford Commercial Club. In 1906 he was elected its president. When he tried to resign three years later, the members would have none of it, calling him “Medford’s grand young man” and observing that “when any distinguished visitors come to the city, (or) when there is any representative delegation for the city, the judge is the one to welcome the one and form a part of the other.”

In 1911, Colvig retired from the practice of law after 30 years as an attorney. He was also allowed to resign as volunteer President of the Medford Commercial Club but was immediately rehired as President and Manager with a salary of $250 a month. His primary responsibility was promoting Medford and the Rogue Valley. Colvig’s efforts are credited with helping to create the Valley’s “spectacular (orchard) boom.”

A 1912 Medford Mail Tribune article naming Colvig to the “Medford Hall of Fame” described him as “the original and only booster” and heralded him for spending “all his time convincing people that the best place on earth is … Southern Oregon.”

The article cited a meeting of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce that Colvig attended. Local members lauded their city in glowing terms. When Colvig was invited to speak, he said that he did not feel he could add anything to the beautiful tributes paid to Los Angeles, but that he was reminded of the following story:

“A party of Los Angeles people who had departed this vale of tears were being shown through the Celestial Regions. As St. Peter pointed out the pearly gates and golden streets their admiration was unbounded, and they expressed themselves with such exclamations as ‘Beautiful’; ‘This reminds us of Los Angeles’; ‘This is just like home.’ As they proceeded, they came to a beautiful place wherein a group of people were chained to the floor with heavy chains. Upon asking St. Peter who these people were, and why they (were) chained, he replied: ‘Those people came from the Rogue River Valley, and we have to chain them to keep them here.'”

After his wife Addie passed away in 1912, Colvig accepted an appointment as tax right-of-way agent from his former client, the Southern Pacific Railroad. The offices were in Portland and he moved there for the next five years before again retiring and returning to Medford where he made his home with one of his daughters.

Colvig remained active and popular as a public speaker with a few more adventures along the way. His opinions were sought on the 1923 silent movie, “The Covered Wagon.” He was Grand Marshall of the state’s Jubilee Parade celebrating the 75th anniversary of Oregon statehood.

In 1926 he was one of the first Valley residents to travel by air to Los Angeles and the subject of news coverage up and down the West Coast. Colvig acknowledged a “nervous fear” along with the desire for “a rousing drink of Hennessey’s Three X.” But he became “enraptured” by Mt. Shasta, seemingly “an island rising from out the great sea”; the Sacramento River looking “like a silver ribbon as it winds its way across the valley miles”; the “patchwork quilt” of cultivated fields; autos moving like “big black spiders”; and houses no larger than “grains of corn.” The flight lasted six hours and 45 minutes.

After that jaunt, Colvig found trains too slow. Describing himself as “kind of a fatalist,” he elected to travel by air when possible, a “resting place on the way to the stars”—a permanent resting place Colvig found in 1936.

Nice profile Ms. Kingsnorth. There is so much to say about my great grandfather, William Mason Colvig, but you capture one of the remarkable aspects of his life very well. His childhood involved riding on horseback and coming across the Oregon Trail by oxen-led covered wagon when he was six years old. He went on to travel by canoe, flat boat, steamer, stage coach, train, car and yes, by plane to visit his famous son, Pinto Colvig, in Hollywood. From covered wagon to riding in a plane–that’s a lot of progress over one lifetime, all of which he fully embraced.

Wonderful comment – thank you so much, Tim Colvig!