Pioneer Profiles – October 2015

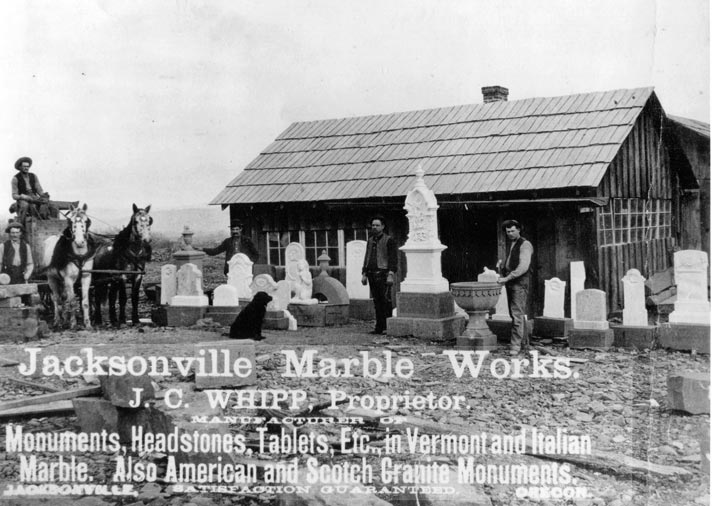

As you tour Jacksonville’s Historic Cemetery during “Meet the Pioneers” on October 9th or 10th, or wander among the tombstones on other occasions, you can’t help but notice the elaborate markers that typify Victorian gravesites. Many of these are the work of stonemason James Carr Whipp. His signature can be seen on some of the finest examples of marble tombstones and monuments in cemeteries throughout southern Oregon.

Whipp, a native of Yorkshire, England, had been apprenticed as a stonemason in his early teens. He had refused to return to school after throwing an ink bottle at his eighth-grade teacher and leaving through the nearest window.

He learned the stonemason craft thoroughly, although it’s not known if he finished his apprenticeship given that he joined the Royal Navy around 1867 when he was 19 or 20. Once his parents realized Whipp was intent on seeing the world, they obtained a place for him in the British Marines. Sailing under the flag of the British West Indies Fleet, Whipp rapidly rose in rank to a top non-commissioned officer rating. (He also won the fleet’s wrestling championship!)

With the fleet sailing between the West Indies, South America and Africa, Whipp did see a good bit of the world, experiencing a number of adventures in the process. He recounted chasing a Dutch slave ship off the African coast. When they stopped the ship and boarded it, all the slaves had been thrown overboard to prevent the vessel from being confiscated. Another incident involved a landing party in Cuba that marched directly between a Spanish firing squad and crew members of an American ship, thus securing the crew’s release.

Whipp was a member of a landing party in Central America sent to rescue a group of British and Americans kidnapped by natives and taken into the interior. He recalled it being the toughest experience he encountered during his naval career. After fighting their way through miles of dense jungle, they did succeed in freeing the hostages. At that point, they were so close to the Pacific Ocean, they decided to keep going.

They were eventually picked up by a British war sloop on its way to British Columbia. It was some months before they were able to return to the Atlantic, via the treacherous waters of Cape Horn, to rejoin their ship. By that time their vessel had been reassigned to Halifax, Nova Scotia. When Whipp and another member of the rescue party came over the side of their home ship, the crew thought they were seeing ghosts.

Whipp’s career almost ended in Halifax. While swimming in the bay, he came close to drowning. He was going down for the third time when he was saved by a friend. Shortly afterwards while on shore leave, Whipp “jumped ship,” boarding an American vessel headed for New York.

It’s not clear how long he stayed in New York, but Whipp was there long enough to take out citizenship papers. Still looking for adventure, he joined the 1st U.S. Calvary in 1873 and was shipped out (again via Cape Horn) to Vancouver, Washington, and later stationed at Fort Walla Walla.

Once discharged from the Calvary, Whipp made use of his earlier training. Portland, Oregon, was booming and a skilled stonemason could find good employment. He worked on most of the early buildings that involved stone work including the old Portland Hotel and The Oregonian newspaper building. He worked on the Oregon City Locks and the Tillamook lighthouse.

At the age of 36, Whipp came to Jacksonville in 1883 to do the stone work on the historic Jackson County Courthouse.

Florence Hoffman Shipley was a widow with two teenage daughters. In addition to teaching school and giving music lessons, she occasionally took in boarders. Whipp became one of her boarders—a permanent one. He married Florence in 1884.

Shortly afterwards, Whipp started the Jacksonville Marble Works. Unfortunately, one of his early creations was the “French cradle” that marks the grave in the Jacksonville Cemetery of J.C.’s and Florence’s first born—Caroline, or “Carrie.” ( J.C. and Florence subsequently had a son and a daughter, born in 1887 and 1890.)

Shortly afterwards, Whipp started the Jacksonville Marble Works. Unfortunately, one of his early creations was the “French cradle” that marks the grave in the Jacksonville Cemetery of J.C.’s and Florence’s first born—Caroline, or “Carrie.” ( J.C. and Florence subsequently had a son and a daughter, born in 1887 and 1890.)

But in addition to gravestones, Whipp built culverts and laid the foundations for many of the bridges in Southern Oregon. In 1887, he turned the Methodist Episcopal Church 180 degrees to face the new North 5th Street thoroughfare, and in 1893 he created a stone mantelpiece that won a blue ribbon at the Chicago World’s Fair.

He also entered into the civic activities of the community with, according to his son, “the ‘take charge’ spirit” that was “envy to a few” and “the chagrin of other local citizens.” Whipp was president of the volunteer fire department for 20 years. He took an active interest in Republican politics, fraternal organizations, and church work. He became a spokesperson for water reclamation that enhanced homesteader irrigation rights and turned his own homestead into a valley showcase.

When Whipp attempted to join the Masonic Lodge, he was black-balled. The individual responsible made no bones about it, saying, “J.C. runs everything else in this town. I’ll be damned if he is going to get the chance to run this lodge.”

However in 1902, after about 15 years of good living in Jacksonville, Whipp was persuaded by a salesman that he should move his business to Ashland. Whipp had to go into debt to make the move and erect a building, shop and showroom. He found himself in competition with an old established firm, and within a few months was in debt to the bank. At 56, he was again starting from scratch.

Whipp spent a winter working part-time at his trade in San Francisco and Los Angeles, then moved his family to Reno, Nevada. In 1905 he homesteaded on an 80-acre tract five miles south of Fallon, Nevada. He knew nothing of farming, but in selecting his plot picked a rough acreage with the tallest greasewood bush. He theorized that the best land was that growing the largest brush, and when irrigation became available for his plot two years later, his homestead became one of the best producers in the valley until Whipp’s death in1927.

Pioneer Profiles is a project of Historic Jacksonville, Inc., a non-profit organization whose mission is helping to preserve Jacksonville’s Historic Landmark District by bringing its buildings to life through programs and activities. Join us on October 3 & 4 for “Victorian Mourning Rituals” tours at Jacksonville’s historic Beekman House Visit us at www.historicjacksonville.org and follow us on Facebook (historicjville) for upcoming events and more Jacksonville history.