Pioneer Profiles – February 2015

As Jacksonville celebrates Chinese New Year this month, we should not lose sight of the original “welcome” given Chinese immigrants when they first arrived in Oregon in the 1850s.

Jackson County greeted the Chinese with a $2-per month Chinese mining tax levied in 1857 and doubled in 1858, and Oregon included a provision in its original 1857 state constitution stating that “no Negro, Chinaman, or Mulatto shall have the right of suffrage.” No non-white was allowed to testify against a white settler until 1862, and when Chinese residents were eventually given voting privileges, they were charged a $5 poll tax. Chinese engaged in trading were charged $50 per month for the privilege. Chinese miners and laborers were beaten, bullied, and even killed while the law and the courts looked the other way.

Despite this institutionalized discrimination, Chinese men came by the thousands, lured by tales of “Gold Mountain.” Some may have drifted to Oregon from California on their own, but most arrived under contract to Chinese labor bosses who then farmed them out to work for white mine owners.

One such prominent Chinese mine boss was Gin Lin. He apparently left China shortly after gold was discovered in California in 1849. By the 1860s, he was in Oregon. Despite state laws prohibiting Chinese property ownership, Lin was able to purchase a claim in 1864 on the Little Applegate River at the mouth of Sterling Creek for $900. He subsequently leased or purchased other “played out” placer mines in the vicinity from white men who had already taken out the easy gold.

Soon many of the laborers Gin had previously contracted to other mine owners came to work for him. Local legend credits him with founding the old mining ghost town of Buncom to house his Sterling Creek mining crew.

Gin was an honest and fair mine owner, even helping some of his men purchase their own claims and insuring their claims were legally recorded and the proper taxes paid. As a result, Lin’s crew was willing to work hard for him. When the placer gold was depleted, they began excavating for gold in old stream beds long since buried in adjacent hillsides. To make the effort profitable, Gin introduced hydraulic mining to Southern Oregon.

Hydraulic mining depends on a reliable water source. Gin’s crews dug hundreds of miles of ditches to divert water from the Applegate River and larger streams through a series of wooden boxes and pipes until it built up sufficient pressure to blast exposed hillsides, sending rock, gravel, and dirt through a series of sluice boxes, separating the gold from the silt and rubble. This legacy can still be seen today in various regional trail systems—the most notable being the China Ditch Trail and the Gin Lin Mining Trail, the latter still showing remnants of Gin’s complex water system and expensive equipment.

Through industry and ingenuity, Gin Lin and his mining company began to play an important role in Southern Oregon’s economy. It also helped Gin amass a fortune. He reportedly took out over $2 million in gold from his various mining claims and had an account worth over $1 million in Cornelius Beekman’s Jacksonville bank.

Gin was well liked by Beekman, and also became friends with several other prominent business leaders, including pioneer photographer Peter Britt, attorney Wes Kahler; and cabinetmaker David Linn.

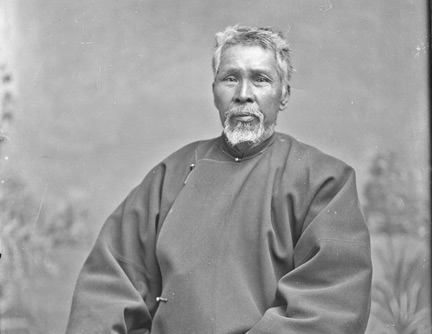

David Linn’s son, Fletcher, described the Chinese businessman in his book, Memories: “Gin Lin was a large, robust character, not at all like the ‘Coolie’ or laboring Chinese who constituted the laboring force in his operations…. On one of his visits to ‘China Town,’ he came across the street to meet father, and introduced himself as ‘Gin Lin…Dave Linn’s cousin,’ and he and father became quite good friends.”

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Gin Lin discarded his pigtail queue, wore Western dress, and spoke English. He loved to drive his buggy with a high stepping horse around Jacksonville.

He also went to great lengths to keep good relations with the white people of the community, even employing several white men in his mines. He shut down his mining operations during summer months so that farmers could use his ditch water for irrigation. And when a Native American burial was exposed, he would order the area to be left undisturbed.

Gin did return periodically to China, each time bringing a beautiful new young “wife” back with him. He would then sell her predecessor to one of his workers. Gin Wye, born in Jacksonville, was the son of Gin’s youngest and last wife, Gen Shen.

No one knows exactly what became of Gin Lin. When his Little Applegate mining operations played out in the 1870s, he purchased additional claims in the Palmer Creek drainage on the Applegate River. Around 1885, he moved on to Josephine County and no longer merited attention from the Jacksonville press.

Gin Lin disappeared from Oregon in the 1880s. One story says that he sold all his Oregon holdings and returned to China in 1894 where he was murdered for his money. Another story says he lived in China with his wife and son for three years before passing away in 1897.

Pioneer Profiles is a project of Historic Jacksonville, Inc., a non-profit whose mission is helping to preserve Jacksonville’s Historic Landmark District by bringing its buildings to life through programs and activities. Visit us at www.historicjacksonville.org and follow us on Facebook (historicjville) for upcoming events and more Jacksonville history.

Thoroughly enjoyed this account as we hiked the Gin Lin Trail. Thank you. C. Wright

[…] Gin Lin was a notable mine boss, contract labor broker, and businessman during the mid- to late 19th century in the Applegate/Jacksonville area. For more details of who Gin Lin is and some of gold rush history see Carolyn Kingsnorth’s article. […]