Pioneer Profiles – November 2019

This year’s Meet the Pioneers tours of Jacksonville’s historic cemetery included several vignettes portraying 19th Century crime and punishment. In one, a man named Matt Shannon had been killed in an 1881 fist fight when his opponent shot him in the head with a concealed gun. A jury declared the murderer “not guilty” on the grounds of “self-defense.” Shannon’s widow bemoaned the “justice” of the jury’s decision, given that Jacksonville at that time was supposedly “no longer a mining camp in the wilderness where brute force and vigilante justice might prevail over the rule of law.”

But perhaps the vignette was scripted on an idealized premise. In his Crime and Punishment in a Mining Town: Jacksonville, Oregon, 1875-1915, the late Professor Joseph Laythe describes a different Jacksonville, one much more tolerant of criminal “peccadillos” in its efforts to both survive and maintain a degree of regional prominence.

Laythe writes, “While America’s Western communities inherited a tradition of American law, abided by the laws of their respective states, and shared the prevailing racial views of the nation, their definitions of ‘crime’ and their methods of law enforcement varied greatly. The geography, demography, and politics of a community shaped its laws and law enforcement in unique ways. The social structures and social norms of a community interacted with specific circumstances to forge unparalleled forms of crime and punishment.”

Jacksonville was a gold rush town created almost overnight following the discovery of gold in the winter of 1851-2. Some of the earliest “business establishments” were “saloons,” typically tents or rough log structures offering necessities and a generous stock of liquor. These saloons offered solace to lonely, hard-working miners. But the prevalence of liquor also attracted an unsavory crop of gamblers and courtesans, fostering the rise of the other two legs of the “Trinity of Vice”—gambling and prostitution.

The town existed because of its transient, mobile, labor force comprised primarily of single males. According to Laythe, its dependence on miners initiated a tolerance of vice, an acceptance of crime, and a leniency towards criminal offenders that suited both its needs and its population.

In the 1850s, Jacksonville had no written law, only a “hastily prepared handful of territorial laws …that had hardly crystallized into shape.” Justice was based on a code of mutual protection; administered without judge, jury or trial; and enforced with bullets. But as the mining population swelled, it became imperative to establish a judicial system.

Residents created the first people’s court in 1852, electing an “Alcalde,” a combination of mayor and judge, to hear disputes and render binding decisions. However, these legal decisions were easily challenged, and in 1853, one thousand miners resorted to “people’s justice.” Upset with the Alcalde’s decision over a disputed mining claim and his refusal to reconsider, they unanimously decided to create another court. They reasoned that if they had the power to create the first court, then they had the right to institute a second court. Law and justice, in Jacksonville, were malleable, not absolute.

As Jacksonville grew and prospered, established laws became essential, replacing the law of the bullet. But these laws applied only to the town’s white population. Native Americans, blacks, Chinese, and Hawaiians were routinely—and legally—discriminated against. Moreover, legal restrictions worked ineffectively against rowdy white males. The regular court, said A.G. Walling, “failed to awe evil-doers, or to suppress outlawry.”

When mining waned, so did the town’s prosperity and attractiveness. By the 1870s, most of the gamblers and courtesans had abandoned the town, but its tarnished reputation remained. Its status in county and state political and economic affairs was fading. In 1883, when the Southern Pacific Railroad bypassed the town, Jacksonville’s fate was sealed.

Abigail Scott Duniway, a prominent suffragette and newspaper editor, was aware of the town’s troubles as early as 1885. She wrote in her newspaper: “Jacksonville is a discouraged town. The blight of its former hoodlumism has eaten into its prosperity like raids of the canker worm…. The town is noted chiefly for its naughty record.”

“Saloons, hurdy-gurdy houses, gambling halls, and bawdy houses are in full blast,” the Democratic Times wrote in 1887, reporting that “the denizens of the place are thugs, thieves, morphine fiends, harlots and squaw men.” Yet, few arrests were ever recorded for vice offenses. Between 1881 and 1887, there were only six arrests for vice crimes, and this trend did not change. In the first eight years of the twentieth century, only seven recorded arrests occurred in Jacksonville for drunkenness, gambling, or prostitution.

City leaders and law enforcers were unwilling to do what was necessary to eradicate crime and control any dangerous elements. According to Laythe, “The pursuit of wealth and power was of foremost importance to Jacksonville’s town leaders, sheriffs included. Controlling crime was a peripheral issue, which only became critical when the interests of the town’s bankers and businessmen were threatened.” He cites various examples.

In 1879, Sheriff William Bybee, whose side business was hog raising, left town for several weeks to sell his pork in northern California. Bybee also had several hydraulic mining claims throughout the county that took him away from the town, in addition to a ferry operation across the Rogue River. In 1876 he was accused of having closed the fords across the river to Sam’s Valley residents, forcing them to cross over on his ferry. Bybee was reelected despite these accusations of malfeasance.

Town Marshal Fred Grob not only served justice in Jacksonville, he also served drinks at his saloon, a self-serving arrangement. While preserving order in his saloon and establishing a safe place to socialize, Grob attracted business away from the town’s less-orderly saloons. He also cultivated a clientele by showing greater leniency toward his drunken patrons.

James Birdsey, Jackson County sheriff between 1888 and 1892, was an active partner in a Jacksonville hardware store. His law enforcement duties came second to his business interests. In fact, his neglect of duty resulted in the destruction of the county jail by fire in July 1889 and the deaths of three prisoners awaiting trial.

Birdsey usually slept at the jail to guard the inmates, but on the night of the fire “bedbugs” supposedly drove him to seek a bed at the U. S. Hotel. While he was “sleeping” at the hotel, the jail caught fire. Both Birdsey’s Republican rivals at the Oregon Sentinel and his Democratic allies at the Democratic Times challenged his motivation for sleeping at the hotel. “As to the ideas of morality entertained by Mr. Birdsey … the world is lax in its interpretation of the seventh commandment and every man is the keeper of his own conscience.”

By the turn of the century, Jacksonville’s only thriving businesses were its numerous saloons and breweries. Crime and the activities associated with it was a necessary ingredient in the town’s survival. City leaders had little incentive to enforce the laws since arresting local drunks, prostitutes, gamblers, and brawlers meant arresting the town’s few gainfully employed men and women.

In April of 1902, Harlow C. Messenger, a longtime resident of Jacksonville, was sentenced to the Oregon State Penitentiary on manslaughter charges for the killing of J. P. Cotton. The presiding judge, the Honorable H. K. Hanna, criticized the jury that heard Messenger’s case. Hanna suggested that the jury purposefully overlooked evidence that demonstrated the defendant’s premeditation. By doing so, the jurors were able to reduce the murder charge to manslaughter and save their neighbor from the gallows.

Sentiment within Jacksonville clearly sympathized with Messenger. By December 1903, 300 residents had petitioned Governor George Chamberlain to pardon Messenger. Included in the petition were the names of nine of the ten jurors who served on the case. The petitioners argued that Messenger’s failing health and his positive reputation warranted a second chance. More importantly, they asserted, his wife and six children desperately needed support. Chamberlain pardoned Messenger, who returned to Jackson County where he lived the remainder of his life.

The trial and pardon of Harlow Messenger reflects the nature of crime and punishment in Jacksonville. Just as had been the case with the town’s first Alcalde and the reversal of the mining claim dispute in 1853, “justice” and the “law” some 50 years later were defined by those in power who also determined what punishments were appropriate.

Laythe concludes, “By 1915, the town lacked the will and ability to stem any ‘crime’ that may have existed. As respectable and wealthy residents moved to Medford … the town’s poorer (and perhaps criminal) class remained. The lower class could simply not afford to move away. In the wake of Jacksonville’s population exodus, the town was left with only its unsavory population. The town had resigned itself to its fate as a mining community on the decline.”

Pioneer Profiles is a project of Historic Jacksonville, Inc., a non-profit whose mission is helping to preserve Jacksonville’s Historic Landmark District by bringing it to life through programs and activities. Visit us at www.historicjacksonville.org and follow us on Facebook (historicjville) for upcoming events and more Jacksonville history.

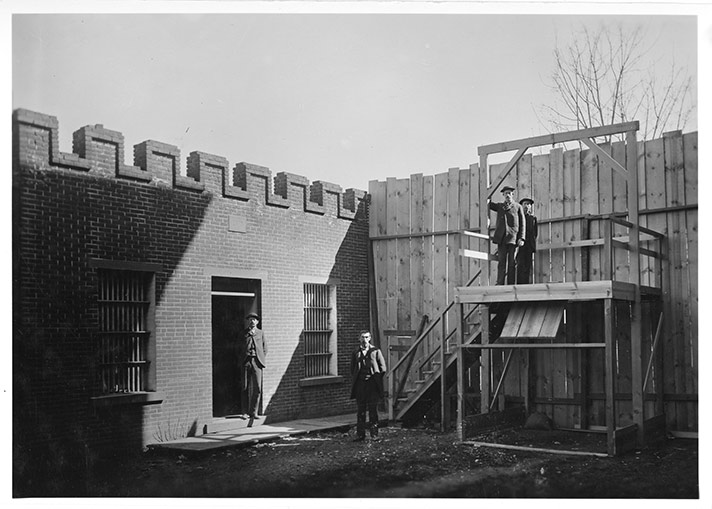

Featured image: SOHS 02139: Scaffold for O’Neil Hanging 1886